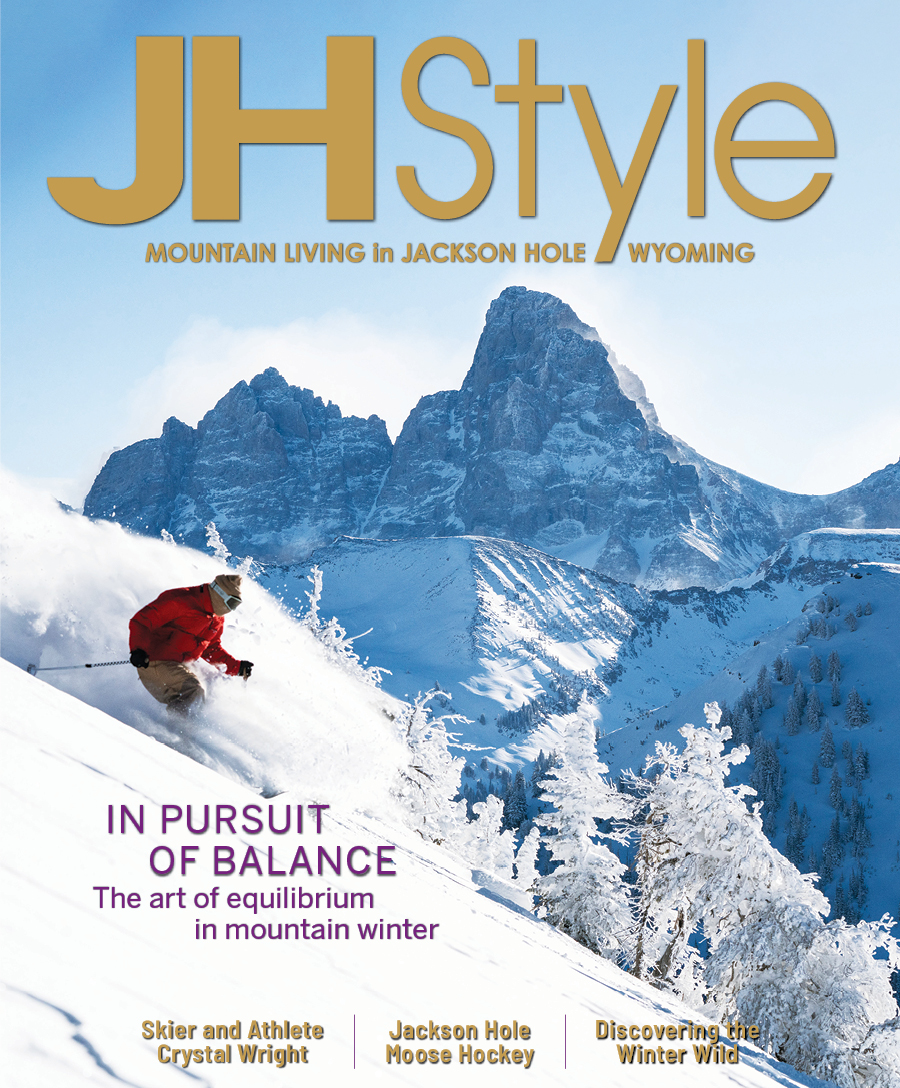

Bringing Back the Buffalo

14 May 2024

Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative works to restore bison to reservation lands

Summer/Fall 2024

Written By: Brigid Mander | Images: David Bowers

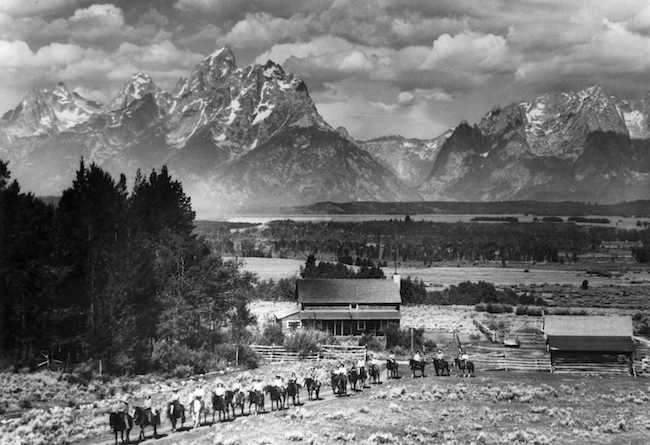

For all their perceived grandeur and glory, the open landscapes that remain in the United States have been missing something very important for almost two centuries: bison. The American bison once roamed North America from modern day Northern Mexico into Canada, and from California to Maine in the tens of millions of animals. As a keystone species, the bison were of tremendous importance ecologically for native plants, birds and other animals.

Modern Americans and tourists to the West, particularly to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, don’t often realize the impact of the loss of bison or even that they are the one native wildlife species that is, to this day, still not classified as wildlife. Yet for Native American people, including the members of Wyoming’s Eastern Shoshone tribe, their absence — both symbolic and practical — has been keenly felt for generations.

Today, dozens of tribes around the nation, including the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapahoe of Wyoming’s Wind River Reservation, have decided to rewrite the script. That means they have taken on the herculean task to rematriate bison back to their traditional homes where they can: on remaining reservation lands. It’s a huge and complex undertaking, with traumatic roots and current land, wildlife and livestock management complications stem- ming from the not too distant past. When European settlers fanned out across today’s Western states, purposeful extermination of the bison was promoted to both starve tribes of a main food source and, as put by the Civil War’s Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan, “Let [the buffalo hunters] kill, skin and sell until the buffalo are exterminated. Then your prairies will be covered with speckled cattle and the festive cowboy.” The near total loss of bison — still referred to as buffalo by tribes — from the landscape and ecosystem was the result.

Jason Baldes, an Eastern Shoshone member, has been spearheading the buffalo rematriation effort for years on the 2.2 million acre Wind River Reservation. As the executive director of the nonprofit Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative, he is tasked with acquiring lands to support buffalo habitat for both tribes and to restore and manage them as wildlife within the Wind River Reservation.

“There is more and better habitat for buffalo on the Wind River Reservation than in Yellowstone, or anywhere else,” Jason says. “It’s perfect habitat, and we are part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. The goal is thousands and thousands of buffalo on hundreds of thousands of acres.” In 2016, the first 10 bison returned to Shoshone lands in over a century. Today, between the Shoshone and Northern Arapahoe, that number is at almost 200 animals.

It’s an admirable and romantic undertaking at first glance. But it’s not as easy as it sounds. Contrary to popular belief, while tribal lands are theoretically sovereign, they are still managed by the federal government via the Bureau of Indian Affairs. “The Bureau of Indian Affairs is a trustee of our lands, and this makes it difficult to change the land back to what we want to use it for,” says Jason. That’s where Jason and the Tribal Buaffalo Initiative come into play: current and future land set aside for the buffalo on the Wind River Reservation must be bought by the nonprofit. They will then be owned and managed for both tribes by that nonprofit, thus evicting the Bureau of Indian Affairs from control. In order to help with the project, the Jackson Hole Land Trust has served as an advisor and fiscal sponsor during the nonprofit’s initial formation and is assisting in fundraising for land purchases.

“Jason has an incredible vision to restore potentially half a million acres for buffalo, but they have to buy back their own land (lost when the Dawes Act of 1887 opened reservation lands to non-tribal homesteading),” says Max Ludington, president of the Jackson Hole Land Trust. “It’s a complex issue of land ownership, but he’s got it all phased out. From an ecological and cultural point of view, this is an incredibly significant and impactful restoration.”

In order to buy all the lands currently for sale within proposed buffalo habitat, the Buffalo Initiative would need about $20 million dollars. Undaunted, Jason fundraises for each parcel at a time. Currently, the tribal nonprofit and the Jackson Hole Land Trust have raised half of the $2 million needed for a new 440-acre acquisition.

In addition to partnering with the local Land Trust and other fundraising, Jason actively pursues grants and partnerships, and attends events with other tribal leaders from around the country, hosted by philanthropic organizations such as the Doris Duke Foundation. For Jason, the Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapahoe and other tribes around the country, the significance of buffalo rematriation to the land can hardly be overstated. To that end, one of Jason’s most important current projects is youth education. “We want to ensure our youth are knowledgeable about their identity and culture. The buffalo are foundational to who we are. It’s very important our young people are connected to the land, plants, animals, water, fish.”

This outreach will increase as the project grows and involves in a large part bringing young tribal members to see the current buffalo on the landscape, and education on traditional relationships with the natural world. For Jason, the return of the buffalo and the ability to reconnect tribal youth with the wilderness, buffalo and horse culture of the past is a symbol of success. “We will show our youth our lifeways, and we are creating leaders who will protect what we have in the future.”