Growing Up Jones

05 Jan 2023

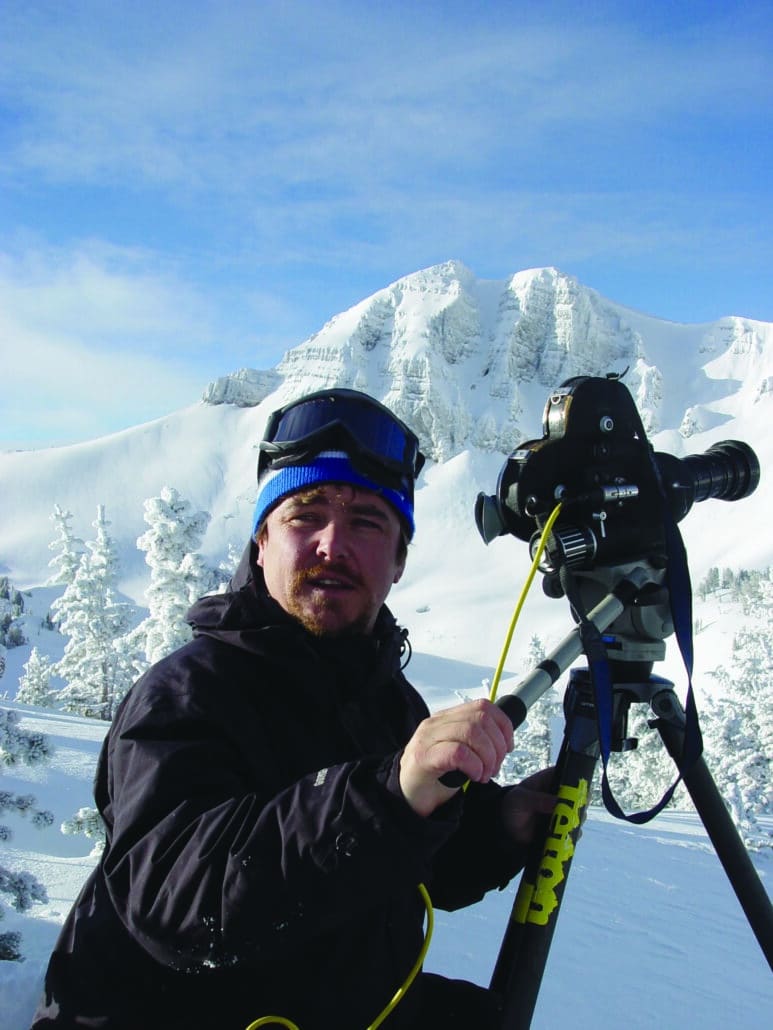

Early backcountry adventures in Jackson Hole shaped the Jones brothers and Teton Gravity Research

Winter/Spring 22-23

Written By: Brigid Mander | Images: Wade McCoy, Chris Figenshau, Mark Gocke, and Tony “Harro” Harrington

Over their three decades in Jackson, Wyo., brothers, skiers, and filmmakers Steve and Todd Jones have had a profound influence on nearly all aspects of skiing and snowboarding culture, from their backyard in the Tetons to across the globe.

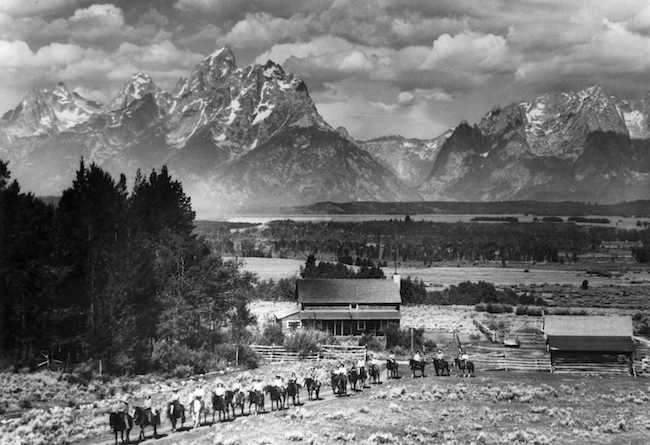

Through Teton Gravity Research (TGR), the company they helped found, and a close collaboration with their brother Jeremy, a professional snowboarder, the impact Jackson’s mountain culture had on the Jones brothers in turn affected the direction and focus of the business around snowsports. And as their movies become more iconic and beloved, they continue to shape the area’s booming backcountry culture today. As skiing and snowboarding culture have evolved in the last 30 years, the Jones brothers and their films have been in the midst of it all: the early days of heli-skiing big peaks and powder in Alaska; taking professional park skiers to the big mountain world; the rise of influential female athletes in action sports; the global search for powder, and most recently, the industry-wide pivot towards human-powered backcountry skiing and safety. Nonetheless, there is no place, and no ski culture, that has both inspired their vision and simultaneously been impacted by their influence than the place Steve and Todd chose as home: Jackson Hole and the members of the local ski community. Growing up by the ocean on Cape Cod, Mass., the Jones kids were always outside, playing and creating their own worlds of adventure. But it was the door opened by another form of water — snow — that enthralled the brothers more than anything else. The trio learned to ski on weekend family trips to Stowe, Vt., sneaking after locals and finding side-country trails unnoticed by the general public. Back then, things weren’t so strict, says Steve from his office at the Teton Gravity headquarters in Wilson, Wyoming. “To us, it felt like a land of untapped adventure.”

By the time Steve was in college, that spirit of adventure, along with the loose perception of boundaries, both physical and conceptual, was deeply imbued in all three brothers. So in the late 1980s, when a college friend who grew up in Jackson invited Steve to visit his home during a school break, Steve was hooked. “I fell in love with the Rockies, and I didn’t want to go back to school,” he says. He took the rest of the 1988-89 winter off to work and ski in Telluride, Colo. News of a series of deep storms back up in Jackson put a quick end to that, however. “I panicked — I quit my job, moved to Jackson. And I never left,” he says — but notes he did finish college eventually, garnering a degree in literature and creative writing from the University of Montana.

The vast, endless possibilities of adventure in the Tetons — first inbounds, and then out of bounds — were immediately clear. “Mostly, we just did [Jackson Hole Mountain Resort (JHMR)] tram laps because there were so few people skiing you hardly needed the backcountry — but also, at that time, the boundaries were closed,” says Steve. Soon, he was part of the small local crew with avalanche gear carefully sneaking out of the boundaries when snow conditions were right, some of whom called themselves the Jackson Hole Air Force. “The access was unbelievable, it was so wild and infinite. I remember the feeling of adventure like it was yesterday.”

In 1990, Todd came for a visit, and he too left college the next year, joining Steve in Jackson. They embraced the wild Jackson lifestyle, funded by washing dishes, waiting tables — anything that started in the evenings, true to the ski bum ethos.

“Jackson then was raw, a much more unwelcoming place — not people-wise, but it was harsh. You had to really want to be here,” says Todd. Those heading out illegally into backcountry terrain from the tram were an even tighter crew, sharing information on snowpack and avalanche conditions; when getting hurt or being irresponsible would call attention to this subculture with far greater reverberations than personal pain.

Adrenaline-fueled practitioners reveled in the snow and terrain — with an understanding of community responsibility.

But Jackson attracted a lot of other ambitious skiers, always after the next wildest skiing frontier. So when professional skier, guide, and fellow Jackson-based adventurer Doug Coombs asked Steve and Todd to guide clients for him in the nascent Alaskan heli-skiing industry of the early 1990s, they jumped at the chance. It quickly became clear to Steve and Todd this kind of skiing — powder, big mountains, and the untamed backcountry — was the future of the sport. “Some of the stuff going on in skiing seemed pretty stale. I didn’t think the boundaries at JHMR would ever open, and we had the vision of making this film company. We thought we could change the world of skiing, capture the spirit and quest for adventure,” says Steve.

By the time Steve was in college, that spirit of adventure, along with the loose perception of boundaries, both physical and conceptual, was deeply imbued in all three brothers. So in the late 1980s, when a college friend who grew up in Jackson invited Steve to visit his home during a school break, Steve was hooked. “I fell in love with the Rockies, and I didn’t want to go back to school,” he says. He took the rest of the 1988-89 winter off to work and ski in Telluride, Colo. News of a series of deep storms back up in Jackson put a quick end to that, however. “I panicked — I quit my job, moved to Jackson. And I never left,” he says — but notes he did finish college eventually, garnering a degree in literature and creative writing from the University of Montana.

The vast, endless possibilities of adventure in the Tetons — first inbounds, and then out of bounds — were immediately clear. “Mostly, we just did [Jackson Hole Mountain Resort (JHMR)] tram laps because there were so few people skiing you hardly needed the backcountry — but also, at that time, the boundaries were closed,” says Steve. Soon, he was part of the small local crew with avalanche gear carefully sneaking out of the boundaries when snow conditions were right, some of whom called themselves the Jackson Hole Air Force. “The access was unbelievable, it was so wild and infinite. I remember the feeling of adventure like it was yesterday.”

In 1990, Todd came for a visit, and he too left college the next year, joining Steve in Jackson. They embraced the wild Jackson lifestyle, funded by washing dishes, waiting tables — anything that started in the evenings, true to the ski bum ethos.

“Jackson then was raw, a much more unwelcoming place — not people-wise, but it was harsh. You had to really want to be here,” says Todd. Those heading out illegally into backcountry terrain from the tram were an even tighter crew, sharing information on snowpack and avalanche conditions; when getting hurt or being irresponsible would call attention to this subculture with far greater reverberations than personal pain.

Adrenaline-fueled practitioners reveled in the snow and terrain — with an understanding of community responsibility.

But Jackson attracted a lot of other ambitious skiers, always after the next wildest skiing frontier. So when professional skier, guide, and fellow Jackson-based adventurer Doug Coombs asked Steve and Todd to guide clients for him in the nascent Alaskan heli-skiing industry of the early 1990s, they jumped at the chance. It quickly became clear to Steve and Todd this kind of skiing — powder, big mountains, and the untamed backcountry — was the future of the sport. “Some of the stuff going on in skiing seemed pretty stale. I didn’t think the boundaries at JHMR would ever open, and we had the vision of making this film company. We thought we could change the world of skiing, capture the spirit and quest for adventure,” says Steve.

The life of a ski bum is an evolutionary path. Jackson has been a massive part of who we became.”

By this time, they’d spent a few years in the tram line, getting to know all the other locals, skiing, and gaining respect. It helped that influential skiers in Jackson were on the same page. “Doug, Howie Henderson [late co-founder of the Jackson Hole Air Force and local legend], and all the Zell siblings, Rick Armstrong, Micah Black, most people supported us,” Steve says.

With Dirk Collins, a skiing and commercial fishing (a job which funded much of their ski adventures and early films) buddy, they invested in a 16mm camera and filmed TGR’s first movie, The Continuum. It premiered in 1996 to a crowd of raucous Jackson locals. By this time, Jeremy, the youngest Jones, had come into his own as an accomplished sponsored snowboarder based in Tahoe, Calif., and reveled in his own show-stopping powder segments in the film.

“Alaska is an outpost for skiers and snowboarders who scoff at the resort-imposed boundaries in the lower 48, seeking freedom and solitude in its untapped mountains,” Dirk narrated in the opening moments of The Continuum’s Alaska segment. This subtle dig highlighted what was happening in Jackson. Its vibrant ski culture needed a bigger outlet than sneaking around and risking arrest for skiing lift-accessed backcountry. In 1999, that all changed. Doug Coombs had been banned from JHMR for life for ducking boundary ropes, and the ensuing rebellious uproar resulted in the unthinkable: the boundaries were permanently opened.

That put an end to the sneaking, and the human-imposed consequences, at least. For another decade, say the brothers, the ski community in Jackson carried on mostly under the radar — the rowdy, rough, and intimidating mountains keeping away any faint of heart, comfort-seeking skiers. “TGR and our movies grew out of the JH Air Force inspiration. We all hung out, we all knew each other, we celebrated skiing and we were all fired up about it together,” says Todd. But as not only their work reached the aspiring mainstream, that of other filmmakers, the ski industry, and resort marketing caught on to the new direction. The floodgates opened, and the adventure of backcountry finally became mainstream.

By this time, they’d spent a few years in the tram line, getting to know all the other locals, skiing, and gaining respect. It helped that influential skiers in Jackson were on the same page. “Doug, Howie Henderson [late co-founder of the Jackson Hole Air Force and local legend], and all the Zell siblings, Rick Armstrong, Micah Black, most people supported us,” Steve says.

With Dirk Collins, a skiing and commercial fishing (a job which funded much of their ski adventures and early films) buddy, they invested in a 16mm camera and filmed TGR’s first movie, The Continuum. It premiered in 1996 to a crowd of raucous Jackson locals. By this time, Jeremy, the youngest Jones, had come into his own as an accomplished sponsored snowboarder based in Tahoe, Calif., and reveled in his own show-stopping powder segments in the film.

“Alaska is an outpost for skiers and snowboarders who scoff at the resort-imposed boundaries in the lower 48, seeking freedom and solitude in its untapped mountains,” Dirk narrated in the opening moments of The Continuum’s Alaska segment. This subtle dig highlighted what was happening in Jackson. Its vibrant ski culture needed a bigger outlet than sneaking around and risking arrest for skiing lift-accessed backcountry. In 1999, that all changed. Doug Coombs had been banned from JHMR for life for ducking boundary ropes, and the ensuing rebellious uproar resulted in the unthinkable: the boundaries were permanently opened.

That put an end to the sneaking, and the human-imposed consequences, at least. For another decade, say the brothers, the ski community in Jackson carried on mostly under the radar — the rowdy, rough, and intimidating mountains keeping away any faint of heart, comfort-seeking skiers. “TGR and our movies grew out of the JH Air Force inspiration. We all hung out, we all knew each other, we celebrated skiing and we were all fired up about it together,” says Todd. But as not only their work reached the aspiring mainstream, that of other filmmakers, the ski industry, and resort marketing caught on to the new direction. The floodgates opened, and the adventure of backcountry finally became mainstream.

Now, the ski community is very different, but broader, and enriched with so many aspects and choices. Resorts are crowded, and ski towns are full of luxury infrastructure, and what was intimidating before is now tamer, says Todd. JHMR now offers backcountry guides to tourists, so they can venture beyond the boundaries with minimal risk. But the core skiers are still out there, those inspired by Todd and Steve’s work, undertaking the adventures in the mountains on their own.

For that reason, the brothers feel an obligation to a new generation of Jackson locals and visitors to emphasize the importance of backcountry safety and responsibility. With mainstream interest, it is no longer a carefully vetted, mentorship experience like when they first were taken under the ropes by other locals impressing the idea of self-reliance. The backcountry is admittedly crowded, thanks to many influences vaster than the Jones brothers, but the end outcome is many people cannot resist the pull of the exit gates — regardless of skill or preparation to undertake even a short adventure.

“There’s a little element of guilt — a lot of people tell us they came here because of our films. We’re very cognizant of our responsibility,” Steve says. “We include more of the whole story and process of being safe and knowledgeable in the backcountry. We want to use our global voice to educate,” not just inspire, he says. That means understanding personal responsibility, and having the tools and skills needed — and using the reach of TGR to showcase their Jackson-instilled values. Where wildlife closures are perceived by some to impede skiing in the Tetons, Steve wants people to know he’s in support of protecting the animals. “There’s plenty of stuff to ride,” he says, and can personally attest to at a level few others can.

“The backcountry has become more and more crowded over the years, and you’ll always see a few yahoos,” Todd says. “But we get excited to see that most people approach the backcountry now in a responsible way.”

That’s a much more complex approach than chasing powder and euphoria with a 16mm camera three decades ago, but so is their home base and original inspiration. “The life of a ski bum is an evolutionary path. Jackson has been a massive part of who we became,” says Todd. “When I look back, I am blown away it all lined up. What evolved around us, here in Jackson, it felt as if we were just going with the flow.”

Now, the ski community is very different, but broader, and enriched with so many aspects and choices. Resorts are crowded, and ski towns are full of luxury infrastructure, and what was intimidating before is now tamer, says Todd. JHMR now offers backcountry guides to tourists, so they can venture beyond the boundaries with minimal risk. But the core skiers are still out there, those inspired by Todd and Steve’s work, undertaking the adventures in the mountains on their own.

For that reason, the brothers feel an obligation to a new generation of Jackson locals and visitors to emphasize the importance of backcountry safety and responsibility. With mainstream interest, it is no longer a carefully vetted, mentorship experience like when they first were taken under the ropes by other locals impressing the idea of self-reliance. The backcountry is admittedly crowded, thanks to many influences vaster than the Jones brothers, but the end outcome is many people cannot resist the pull of the exit gates — regardless of skill or preparation to undertake even a short adventure.

“There’s a little element of guilt — a lot of people tell us they came here because of our films. We’re very cognizant of our responsibility,” Steve says. “We include more of the whole story and process of being safe and knowledgeable in the backcountry. We want to use our global voice to educate,” not just inspire, he says. That means understanding personal responsibility, and having the tools and skills needed — and using the reach of TGR to showcase their Jackson-instilled values. Where wildlife closures are perceived by some to impede skiing in the Tetons, Steve wants people to know he’s in support of protecting the animals. “There’s plenty of stuff to ride,” he says, and can personally attest to at a level few others can.

“The backcountry has become more and more crowded over the years, and you’ll always see a few yahoos,” Todd says. “But we get excited to see that most people approach the backcountry now in a responsible way.”

That’s a much more complex approach than chasing powder and euphoria with a 16mm camera three decades ago, but so is their home base and original inspiration. “The life of a ski bum is an evolutionary path. Jackson has been a massive part of who we became,” says Todd. “When I look back, I am blown away it all lined up. What evolved around us, here in Jackson, it felt as if we were just going with the flow.”