Flavors of Jackson Hole

26 Jul 2021

Influences from natives of the Grand Tetons shape the culinary dishes of today

Summer/Fall 2021

Written By: Melissa Thomasma | Images: Mark Gocke and Madison Webb

When Davey Jackson and other fur trappers first arrived in Jackson Hole in 1827, there were no permanent indigenous settlements in the valley — but not because Native people didn’t treasure this area.

The opposite, in fact. They valued the valley and its surrounding resources and journeyed to the area seasonally. Mountain Shoshone, Arapahoe, Crow, Kiowa, Lakota and Cheyenne tribes all have deep historical connections to the land surrounding Yellowstone. But knowing that winters at this elevation were lengthy and brutal, they utilized the landscape when it had the most to offer, and wisely passed the colder months elsewhere. Though it may be surprising when you glance out at the swaths of hard-scrabble sagebrush and jagged peaks, these Native peoples found abundance in the Jackson Hole landscape — a bounty that is still present, if you know how to look. The seasons bring an ever-evolving array of botanical and animal-derived food and medicine; migrating game like elk and deer, plump camas and biscuit-root plants, and berry bushes hanging heavy with sweet clusters of huckleberries, serviceberries, and chokecherries. Native people also ascended to higher elevations, collecting the nutrient-dense seeds from whitebark pine and harvesting wild trout and white sh from streams, lakes, and rivers. Traditional means of preservation allowed the Native people to utilize the bounty of their summer and fall forage all winter long. Large strips of meat and fish were hung to dry in the sun or over the smoke of campfires. Berries and roots, dried and pounded, were often mixed with animal fat to create pemmican — a calorie and flavor-dense patty that was nutritious and easily portable. When the first white explorers and trappers arrived in the valley, they ate much like other trappers of the day — their motto was “meat is meat” — a mentality that led them to eat all kinds of critters to survive. In those days, beaver, rabbit, sage grouse, bear, and other game was always on the menu. Their diet was supplemented by what they could bring with them from their infrequent brushes with civilization, including tinned meats, hard breads, and other preserved goods that wouldn’t spoil quickly. As more white settlers came to the valley, Native peoples largely lost access to Jackson Hole and its culinary resources. The settlers both took advantage of the area’s wild food sources and brought new foods to the region. Until the late 1950s, dinner plates in Jackson Hole were rooted deeply in what could be harvested, made, or grown locally. Many families relied on elk and moose to survive the winter, as well as preserved trout and white fish. Backyard gardens provided nutrients during the summer, while harvested wild berries were used to make jams and preserves. Sourdough and home-baked breads and hotcakes were a staple. Some longtime locals recall the last delivery of fruit and fresh vegetables arriving from Utah each fall: a bounty that locals processed and canned to last throughout the unforgiving winter.

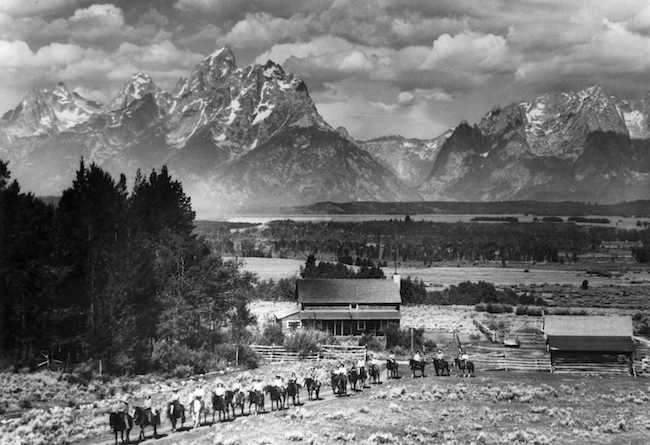

An important element of Jackson Hole’s culinary heritage is that of the dude ranch. In 1908, Lewis Joy and Struthers Burt opened JY Dude Ranch, Jackson Hole’s first guest ranch. The model, which was innovative at the time, was a working ranch that hosted guests who wanted to enjoy the iconic cowboy lifestyle for a few weeks. These guests, however, expected something more re ned than a can of corned beef or room-temperature beans. Thus, was the dawn of Jackson Hole as a destination for pleasure — a place where people came to marvel in the natural beauty and thoroughly enjoy themselves. This is clearly a tradition that has lasted, as the valley is now home to award-winning chefs who craft international fare that includes everything from sushi to Lebanese and Italian.

And yet — though some of the ingredients and flavor profiles have changed — there are still many ways in which Jackson Hole’s culinary scene has endured in a way that’s faithful to tradition. Many local families feed themselves with elk, deer, or bison that was hunted in the wild. Smoked or grilled trout, from the Snake River or Jackson Lake, is not an uncommon feature at a backyard barbecue. And you’d be hard-pressed to find a local who doesn’t have a frozen cache of huckleberries — which are carefully doled out in pancakes and muffins and sprinkled on ice cream throughout the valley’s most frigid months. (It’s a taste of summer like no other.)

Until the late 1950s, dinner plates in Jackson Hole were rooted deeply in what could be harvested, made, or grown locally. Many families relied on elk and moose to survive the winter, as well as preserved trout and white fish. Backyard gardens provided nutrients during the summer, while harvested wild berries were used to make jams and preserves. Sourdough and home-baked breads and hotcakes were a staple. Some longtime locals recall the last delivery of fruit and fresh vegetables arriving from Utah each fall: a bounty that locals processed and canned to last throughout the unforgiving winter.

An important element of Jackson Hole’s culinary heritage is that of the dude ranch. In 1908, Lewis Joy and Struthers Burt opened JY Dude Ranch, Jackson Hole’s first guest ranch. The model, which was innovative at the time, was a working ranch that hosted guests who wanted to enjoy the iconic cowboy lifestyle for a few weeks. These guests, however, expected something more re ned than a can of corned beef or room-temperature beans. Thus, was the dawn of Jackson Hole as a destination for pleasure — a place where people came to marvel in the natural beauty and thoroughly enjoy themselves. This is clearly a tradition that has lasted, as the valley is now home to award-winning chefs who craft international fare that includes everything from sushi to Lebanese and Italian.

And yet — though some of the ingredients and flavor profiles have changed — there are still many ways in which Jackson Hole’s culinary scene has endured in a way that’s faithful to tradition. Many local families feed themselves with elk, deer, or bison that was hunted in the wild. Smoked or grilled trout, from the Snake River or Jackson Lake, is not an uncommon feature at a backyard barbecue. And you’d be hard-pressed to find a local who doesn’t have a frozen cache of huckleberries — which are carefully doled out in pancakes and muffins and sprinkled on ice cream throughout the valley’s most frigid months. (It’s a taste of summer like no other.)

Chefs across the valley hold local foods in high regard — many are mindful to incorporate native proteins like elk and bison, and utilize the brief growing season’s bounty of fresh. Like the generations of people who came before them, local chefs seek opportunities to find connections to the landscape and all its resources in a way that is meaningful and unique. And yet, the influence of the dude ranch experience echoes. We don’t just build menus on what’s easy and filling; we seek to make eating a welcoming and connecting experience for everyone in the valley, whether they’re just passing through, here for the season, or for the long haul. Food isn’t simply about survival — it’s one way people can experience this part of the world.

Staying connected to our food sources is a way to honor the generations of humans who experienced and treasured this valley before us. There’s something powerful about the chance to enjoy berries or mushrooms that were soaking up mountain sunshine just hours before, or the inimitable flavor of pan-seared elk that grazed and grew in this valley.

These flavor experiences offers us an opportunity to connect with the landscape on a deeper level, as well as honor the heritage of those before us.

And — equally important — it’s an invitation to slow down, appreciate, and enjoy. ■