Jackson Hole Land Trust’s Max Ludington works to preserve our legacy landscape

01 Oct 2023

Prioritizing conservation and open space

Summer 2023

Written By: Lexey Wauters | Images: Briley Pickerill

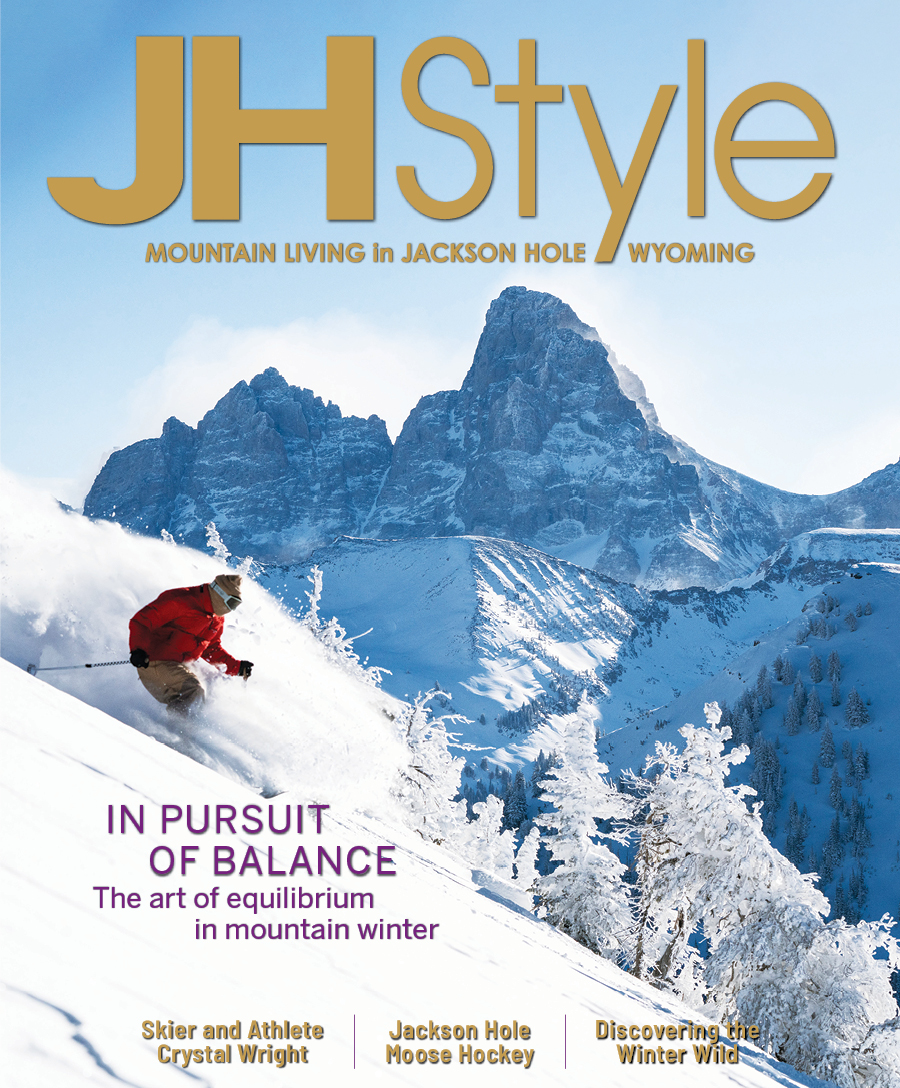

What is immediately striking about viewing the Jackson valley from above is what isn’t there. Development. Houses. Pavement. With few exceptions, the landscape seen from the top of the Aerial Tram (10,450 feet above the valley floor) looks much as it did a century ago.

There are wide open spaces braided with waterways. Stands of cottonwoods and stretches of sagebrush look much the same as they did when the Native American population occupied this valley. These vistas look this way today as a result of a long history of stewardship and protection. The Jackson Hole Land Trust and its president, Max Ludington, is a vital part of this tradition.

Like many before him, Max moved to the Tetons for a seasonal job. Inspired by the Wyoming landscapes before him, he completed a Master’s in Environmental Science at UC-Santa Barbara, California, and returned to devote his career to preservation of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. During this time, while working on public land projects, Max came to realize that the biggest threats to open spaces were outside the borders of our public land. Private lands adjacent to parks, along rivers, and within migration corridors were most threatened. The Land Trust’s mission to preserve open spaces and critical wildlife habitat aimed straight at these threats. Two years ago, when the president position became available, Max joined the Jackson Hole Land Trust.

The Land Trust works with private landowners to place tracts of land into protective easements. The easement conditions are arrived at through conversations between the landowner and the Land Trust; generally they protect working lands, wildlife habitat and open space while limiting development. Original uses — ranching, hunting and fishing — are protected. Some easements are donated; others are purchased.

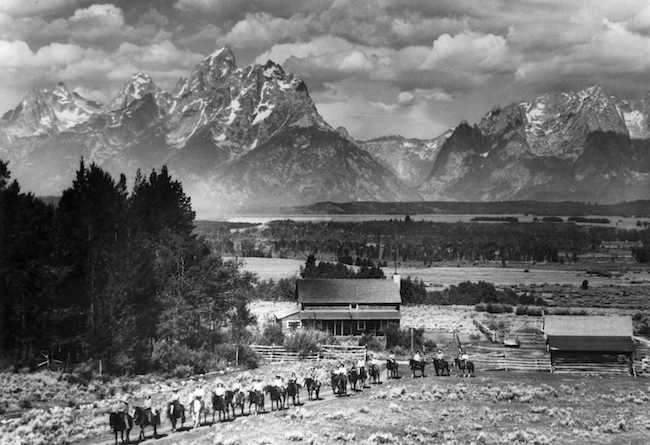

Max is quite clear that “conservation and stewardship doesn’t start with an easement or the Land Trust. Stewardship has been ongoing for generations; the reason there are conservation values to protect is that this land has been taken care of by the long line of people who have called this valley home for thousands of years.”

Max has come to appreciate that families who steward this land today feel tied it; it’s part of their identity. The easement “allows those conservation values to be preserved within a legal document that can be upheld,” Max states.

One stunning story is that of the Walton Ranch easements. The largest easement in Teton County, 1,840 acres of the ranch is under protection. These easements were placed over a number of years starting in 1983. Max shakes his head in wonder as he shares that, “the first easement, they didn’t even take a tax deduction.” Max goes on to explain, “that is all about this landowner’s care for the land, their love of this valley and what it has.”

For Max, one of the most stirring examples of conservation’s impacts is the stretch of the Snake River that runs through the valley. As it leaves Grand Teton National Park, the Snake winds through mostly private land as it flows south. The Land Trust has worked with numerous river adjacent owners including Snake River Ranch and the U Lazy U to place protective easements. As a result, this commonly floated stretch of the Snake, with development just out of view, boasts a healthy riparian corridor that supports robust populations of bald eagles, osprey, beaver, trout and herds of elk, mule deer and moose.

When asked about upcoming legacy projects, Max is coy. Out of respect for the landowners, the Land Trust doesn’t share specific project details until easements are complete. Some projects are celebrated with ceremonies; for other properties, a quiet toast over dinner may be all the ceremony needed. Events like the Land Trust’s Annual Community Picnic each year on the second Sunday of August are an opportunity to celebrate project momentum and partners.

With reverence and pride, Max states, “All of the keystone species are still present in this ecosystem. This is the only place in the lower 48 where that is true.” Which means, even with over 20,000 acres under easement protection in Teton County, “there is still work to be done.” The partnership between landowners, federal management agencies and organizations like the Land Trust will ensure that for generations, a way of life and a legacy, is preserved.

HOW TO GET INVOLVED

For more information on the work that the Jackson Hole Land Trust is doing and to learn how you can get involved, please visit their website at jhlandtrust.org or email info@jhlandtrust.org.