Jackson Hole ranchers host annual branding events

26 Aug 2023

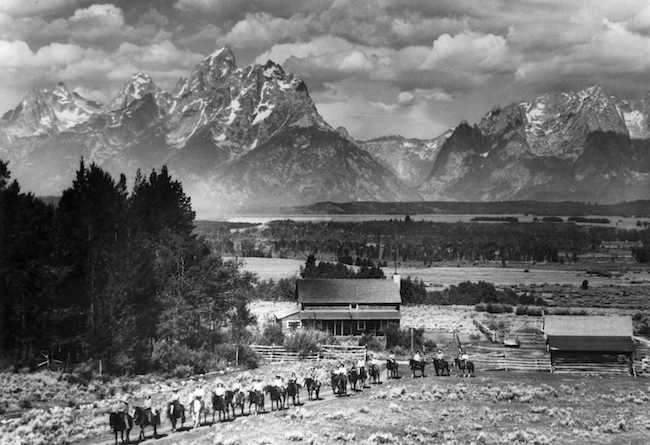

The centuries-old tradition now represents the operation’s history

Summer 2023

Written By: Emmie Gocke | Images: Mark Gocke

Perhaps cowboy poet Red Steagall best described the lore, duty and pride attached to a cattle outfit’s brand, the symbol burned onto the hip of stock to denote ownership, in his famous lines: “Son, a man’s brand is his own special mark that says this is mine, leave it alone. You hire out to a man, ride for his brand and protect it like it was your own.”

The old cowboy adage “ride for the brand” means to take pride in the unwavering dedication and stewardship required by the cowboy way of life and to protect that lifestyle and the cattle themselves with fierce loyalty and hardened vigor. The symbols and letters that denote an outfit’s brand burn much deeper than the singed hairs of the cattle they adorn. It represents the outfit’s history, family, tradition, name, and everything it took to build it. In the early days of the American cattle frontier, the sweeping plains, deserts and mountains between Mexico and British Columbia were void of the barbed wire fences often seen criss-crossing the American West today. Brands were essential for cowboys to identify their stock if they mingled with another herd, and deter cattle rustlers from making for the sale barn with stolen steers. Although many ranchers still have cattle out on the open range, brands now largely represent the history and quality of the outfit raising the cattle. “Brands affect the price,” says Jackson rancher and cowboy, Shane Lucas. Buyers build decades-long relationships with ranchers, buying their calves year after year because “they like what they get.” The quality and consistency associated with a brand build the brand’s reputation. “Like Louis Vuitton,” says Shane, “you’re not buying a purse, you’re buying a name.” In recent years, as the traditions of the American West have been romanticized in the public eye, brands themselves have started selling for prodigious prices. The right to a brand steeped in history, or owned by a well-known ranching family could fetch upwards of $50,000. But for many families, brands are passed down like treasured family heirlooms; even if they’re no longer placed on cattle, family members continue to pay the fee to keep their ancestors’ brands registered for the sake of history and tradition. Shane’s family has several brands “people couldn’t write a big enough check to own. My family wouldn’t ever release it.” Those brands catalog the long history Shane’s family has of ranching in Jackson Hole, going back to the 1890s when they first homesteaded along Spring Gulch and the Snake River Corridor. Instead of family reunions once a year, the Lucases have their annual brandings — the day when every calf is marked with the family brands. “Everyone comes out for it — moms, dads, aunts, uncles, grandmas, grandpas,” and not without incentive. After the work is done, “we’ll have a lunch of sandwiches, chips, snacks, soda and beer. Beer is an all day, from start to finish sort of deal. That’s how you get people to come to the branding,” Shane jokes. Branding day is no small feat. First calves, sometimes hundreds, are rounded up on horseback and sorted from the cows. Then, with the branding irons glowing red hot in a bed of coals, ropers on horseback loop the calves heels and drag them toward waiting “wrestlers” who hold the calves for the coming iron, and a series of shots like vaccines and antibiotics. If the calf is a bull-calf, it will be castrated or banded in one fell-swoop. Each job fits into a hierarchy, with the ranch owner holding the iron, older family members giving shots, and the young and spry doing the wrestling. Roping is one of the most desirable positions out of the dust, but it’s also the easiest spot to lose. Only the best ropers at the branding are allowed to stay on horseback. “There’s little tiny kids and that’s all they do, they don’t rodeo or anything, they just ranch and rope everything, and they’ll out rope someone all day long,” says Shane.

Aside from a family reunion and a casual roping competition, branding day is also a celebration of the success of calving season — the most grueling time of year for ranchers. “You’ve been up and tried to keep everything alive and then you finally get to put your brand on them,” Shane recalls, thinking of the long nights spent in the calving barn helping cows to deliver safely.

Shane continues to help rope and wrestle at his family’s brandings every year, but now he has his own brand thrown into the mix. The WW brand — signifying his new company, Wyoming Wagyu — was a graduation gift from his mom after he completed his degree in ranch management at the University of Wyoming. Shane plans to bring his premium Wagyu beef to market in Jackson Hole this fall, hoping to catch the eyes of local private chefs and high-end distributors. With a long legacy of cowboy heritage behind him, we can be sure that Shane’s WW will be a brand to remember.

Branding day is no small feat. First calves, sometimes hundreds, are rounded up on horseback and sorted from the cows. Then, with the branding irons glowing red hot in a bed of coals, ropers on horseback loop the calves heels and drag them toward waiting “wrestlers” who hold the calves for the coming iron, and a series of shots like vaccines and antibiotics. If the calf is a bull-calf, it will be castrated or banded in one fell-swoop. Each job fits into a hierarchy, with the ranch owner holding the iron, older family members giving shots, and the young and spry doing the wrestling. Roping is one of the most desirable positions out of the dust, but it’s also the easiest spot to lose. Only the best ropers at the branding are allowed to stay on horseback. “There’s little tiny kids and that’s all they do, they don’t rodeo or anything, they just ranch and rope everything, and they’ll out rope someone all day long,” says Shane.

Aside from a family reunion and a casual roping competition, branding day is also a celebration of the success of calving season — the most grueling time of year for ranchers. “You’ve been up and tried to keep everything alive and then you finally get to put your brand on them,” Shane recalls, thinking of the long nights spent in the calving barn helping cows to deliver safely.

Shane continues to help rope and wrestle at his family’s brandings every year, but now he has his own brand thrown into the mix. The WW brand — signifying his new company, Wyoming Wagyu — was a graduation gift from his mom after he completed his degree in ranch management at the University of Wyoming. Shane plans to bring his premium Wagyu beef to market in Jackson Hole this fall, hoping to catch the eyes of local private chefs and high-end distributors. With a long legacy of cowboy heritage behind him, we can be sure that Shane’s WW will be a brand to remember.