Nature’s calendar

03 Oct 2022

A changing of the seasons through the eyes of Jackson Hole’s migrators

Summer 2022

Written By: Emmie Gocke | Images: David Bowers

It’s one of the first warm days of March. The sun is clinging to its post longer with each sunrise and dissipating the winter chill like fog on a misty morning.

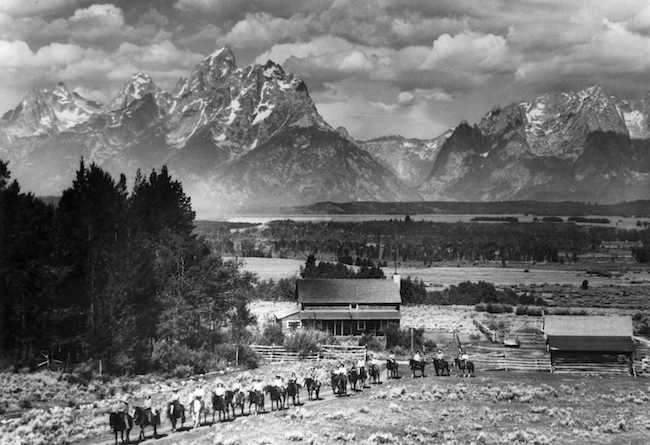

The warm Chinook breeze, the excited chattering of birds, the scents of exposed mulch and rotting grass, all raise together in a chorus that says: it’s time to awaken, stretch, and move. I lace up my dusty running shoes and hit the gravel-sprayed bike path behind my house. At first, I think it’s a trick of the light — a streak of blue too brilliant and quick to be true — but then I see it again: a mountain bluebird diving playfully in the golden sunlight. They are the first of the great migrators to hear the universal call for movement and make their way back to Jackson Hole. Carved into the dark mud bordering the path are the hoof prints of elk, pointed for the hills. They have heard the call too, and slowly begin to trickle from the flat lowlands to their calving grounds in the greening meadows. The great wildlife migrators of Jackson Hole are once again on the move. As spring marches toward summer, the birds in the area begin to multiply. Sandhill cranes arrive in early April, their throaty calls reverberating across lowland marshes. Most continue north to Yellowstone and beyond, but some settle down in Jackson Hole, returning to their nesting grounds with the same mates year after year. Great blue herons are also returning to their rookeries, enormous nests bunched together in cottonwood groves. And the haunting call of the common loon may be heard drifting across recently defrosted lakes. Meanwhile, the elk continue their trek north across Antelope Flats to the high country of the Gros Ventre or along the Snake River corridor to Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks. Bison also undertake migrations from their winter ranges to the calving meadows of Grand Teton National Park. With the shift from April to May, pronghorn begin to arrive in Grand Teton National Park after completing the 150-mile trek from the sagebrush lands near Big Piney. Their white and orange pelts can be seen threading across the brilliant red soil and emerging green plant life of the Gros Ventre. Mule deer are also great long-distance migrators. They pour into the Jackson Hole high country from the south, north, and east, following the receding snow line. In their migration, mule deer cover huge swaths of Wyoming, traveling from the Red Desert to the Hoback Basin and from the plains south of Kemmerer to the northern Wyoming Range. In the spring of 2016, University of Wyoming researchers were astounded by the 242-mile trek of a single doe mule deer across western Wyoming.

The large predators of Jackson Hole are hot on the heels of the migrating ungulates, looking for food to feed their family. The year’s wolf pups are old enough to leave the den and move with the pack in pursuit of migrating elk and deer. Grizzlies and mountain lions may push upward to higher ground pursuing the herds and evading the coming summer heat.

Summer has truly arrived in the valley when the first western tanagers appear in early June. These migratory songbirds add bright splashes of color to the landscape with their brilliant yellow plumage and the males’ red heads. When the Snake River’s flow peaks in mid-June, cutthroat trout will be making their annual migration to spawn in the small spring creeks feeding the Snake’s tributaries. They’ll remain in the clear “small water” until runoff dips back down.

Meanwhile, the big-game migrators are settled into their high-country summer ranges, where food is plentiful and vast forests offer an escape from heat, insects, and pursuing predators. Elk, moose, deer, and bighorn sheep mothers have found sweeping meadows to nurture their new- born calves, fawns, and lambs.

August brings the arrival of one of the most important migratory insect species to the eco-system. Army cutworm moths travel hundreds of miles from the great plains and settle by the thousands in the crevices of talus slopes above the Jackson Hole valley. Grizzly bears travel great distances to gorge themselves on the protein-rich insects as they begin packing on fat for winter.

After a season of plenty, the days grow shorter and early-morning frost begins to form on high-elevation plants. The call to move is sounding again, and the great migrants are stirring. The ungulates rub the velvet from their fully grown antlers as bugles begin to split the air. Big-game males and females gather for the final flourish of summer: the rut. When the mating draws to a close, they flow back along the migration corridors toward their winter range.

These species have followed the well-worn paths in and out of Jackson Hole for centuries. They hear and heed the universal call for movement. As the animals begin to populate the lowlands, where we make our homes, we know it’s time to slow down and settle in for winter.

In their migration, mule deer cover huge swaths of Wyoming, traveling from the Red Desert to the Hoback Basin and from the plains south of Kemmerer to the northern Wyoming Range. In the spring of 2016, University of Wyoming researchers were astounded by the 242-mile trek of a single doe mule deer across western Wyoming.

The large predators of Jackson Hole are hot on the heels of the migrating ungulates, looking for food to feed their family. The year’s wolf pups are old enough to leave the den and move with the pack in pursuit of migrating elk and deer. Grizzlies and mountain lions may push upward to higher ground pursuing the herds and evading the coming summer heat.

Summer has truly arrived in the valley when the first western tanagers appear in early June. These migratory songbirds add bright splashes of color to the landscape with their brilliant yellow plumage and the males’ red heads. When the Snake River’s flow peaks in mid-June, cutthroat trout will be making their annual migration to spawn in the small spring creeks feeding the Snake’s tributaries. They’ll remain in the clear “small water” until runoff dips back down.

Meanwhile, the big-game migrators are settled into their high-country summer ranges, where food is plentiful and vast forests offer an escape from heat, insects, and pursuing predators. Elk, moose, deer, and bighorn sheep mothers have found sweeping meadows to nurture their new- born calves, fawns, and lambs.

August brings the arrival of one of the most important migratory insect species to the eco-system. Army cutworm moths travel hundreds of miles from the great plains and settle by the thousands in the crevices of talus slopes above the Jackson Hole valley. Grizzly bears travel great distances to gorge themselves on the protein-rich insects as they begin packing on fat for winter.

After a season of plenty, the days grow shorter and early-morning frost begins to form on high-elevation plants. The call to move is sounding again, and the great migrants are stirring. The ungulates rub the velvet from their fully grown antlers as bugles begin to split the air. Big-game males and females gather for the final flourish of summer: the rut. When the mating draws to a close, they flow back along the migration corridors toward their winter range.

These species have followed the well-worn paths in and out of Jackson Hole for centuries. They hear and heed the universal call for movement. As the animals begin to populate the lowlands, where we make our homes, we know it’s time to slow down and settle in for winter.