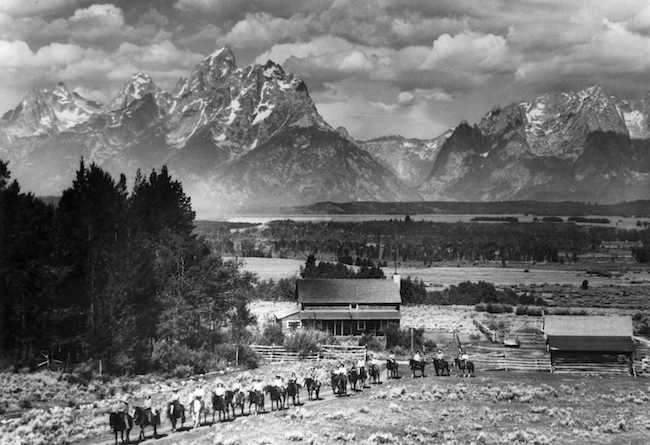

Protecting the Land

07 Oct 2019

Andrews Leads Organization Saving Open Space

Summer 2019

Written By: Kelsey Dayton | Images: David Bowers and Courtesy Hatchet Ranch-Jansen Gunderson

Laurie Andrews has always loved open space. Growing up in California, her family home sat near a ranch where she was allowed to play. When she learned the ranch sold, she cried. She was just 5 years old.

“It’s where I found contentment and where I felt alive,” she says. “I just always felt that connection to land and felt really sad when we lose land.”

Open space is not just a luxury, it’s a need, according to Andrews, who is the president of the Jackson Hole Land Trust. And once it’s gone, it’s gone forever. Andrews knows.

After the ranch near her family’s home sold, they moved to a peach orchard about 90 miles from San Francisco. People were “cavalier” about the then-rural area, she says, and they didn’t plan for growth or protect open space.

“We lived out in the middle of nowhere at the time, and people thought it was never going to be developed,” she says.

Today it’s a bedroom community for San Francisco and Sacramento and unrecognizable from how it was when Andrews was a kid. It’s a lesson she’s internalized in her work to protect open space in Jackson.

Andrews spent her early professional career fundraising for a hospital in California. Then, after several years in that role, she went on her first backpacking trip in Alaska. It inspired her to change her life. “I was like ‘I’m going to live, and I’m going to live very differently,’” she says.

When she returned, she took a job with the Nature Conservancy and moved to San Francisco and then Seattle. In 2003, she moved to Jackson to work on land easements for the Nature Conservancy. Two years later she became executive director for the Jackson Hole Land Trust, and she is currently in the role of president.

“The land trust is such a part of the fabric of Jackson and Wyoming, and it was a place I could make a difference in this community,” Andrews says.

In the last 14 years she’s shepherded a variety of projects to fruition, including Rendezvous Park, a gravel pit transformed into a 40-acre, family-friendly, year-round park. The project exemplifies a shift in the organization’s role in the community. It still works with large ranches on traditional conservation projects, but it also works to create open space every person in the community can use, even if only to find a quiet place to sit for 10 minutes. One of the organization’s latest efforts is the “Save the Genevieve Block” project, which focuses on preserving a historic block in downtown Jackson.

Andrews’ job changes as Jackson grows and evolves, which means it’s never boring and never seems to slow.

When she’s not working, Andrews is often climbing mountains. She recently climbed Gannett Peak—Wyoming’s highest mountain—as well as summited Mount Kenya in Africa.

“Climbing has to be the most Zen thing in the world,” she says. “It’s a really great thing for me, being in the moment.” And it’s yet another way she’s connected to land.