Pushing boundaries in Jackson Hole

12 Dec 2023

The Tetons have long inspired a more ingenious, determined and athletic community

Winter/Spring 23-24

Written By: Brigid Mander | Images: Mark Gocke

The Teton Range and the valleys surrounding its dramatic uplift have offered drama and serenity, adventure and safe harbor, as well as inspiration to people for thousands of years. But it’s never been an easy place to live. Winter is long, harsh and cold, summer brief, and the topography unforgiving all year long.

For some, it’s enough to look and admire from the safe valley floor. But for others, the alpine heights, especially in the ethereal embrace of deep snow and ice, offer an invitation to be the best version of themselves, to push personal limits, and for many, to work fiercely to preserve and protect the natural gifts. It’s a mentality that, historically, has been inextricably linked with life in the Jackson Hole valley.

Once part of the vast area the Eastern Shoshone and other tribes called home, the valley provided ample hunting and sustenance — along with evidence they were climbing high into the Tetons long before Americans of European descent arrived.

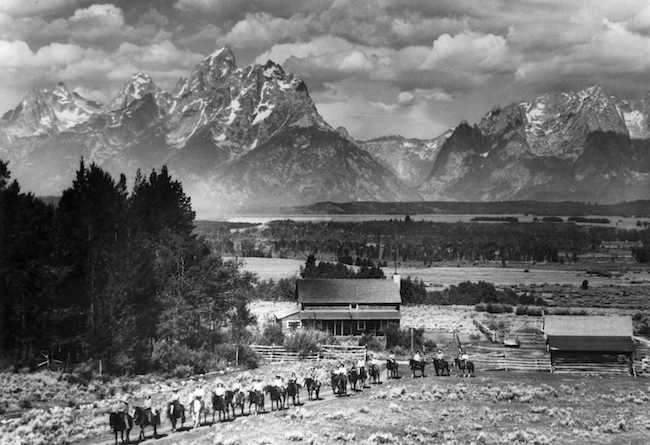

When those first year-round residents of European descent arrived and claimed land in the 1880s, from the get-go it seemed the extraordinary difficulty of surviving — much less prospering — all year long by necessity minted a tougher, more ingenious and determined sort of person. Hardships pushed the new valley residents to their limits. Many gave up and left, but those who stayed figured out how to live as well as prosper in and with nature, and built a community that both produced and attracted famous mountain athletes and a precedent-shattering conservation ethic to help preserve the valley that had given them their strengths.

Unusually for ranchers, many early residents developed an affinity for the existing wildlife, and took unprecedented actions such as feeding elk in winter after their traditional forage was lost to haying operations and the human presence. Sharing, instead of taking, was also novel: the locals set aside over 24,000 acres of prime valley land in 1912 for elk and other native wildlife. Parts of the landmark 1974 Wilderness Act were written at Mardy and Olaus Murie’s cabin at the base of the Tetons. That care and wonder the landscape inspired led to an incredible conservation and exploration legacy that still thrives today, and one which becomes ever more important in the face of unrelenting development pressure.

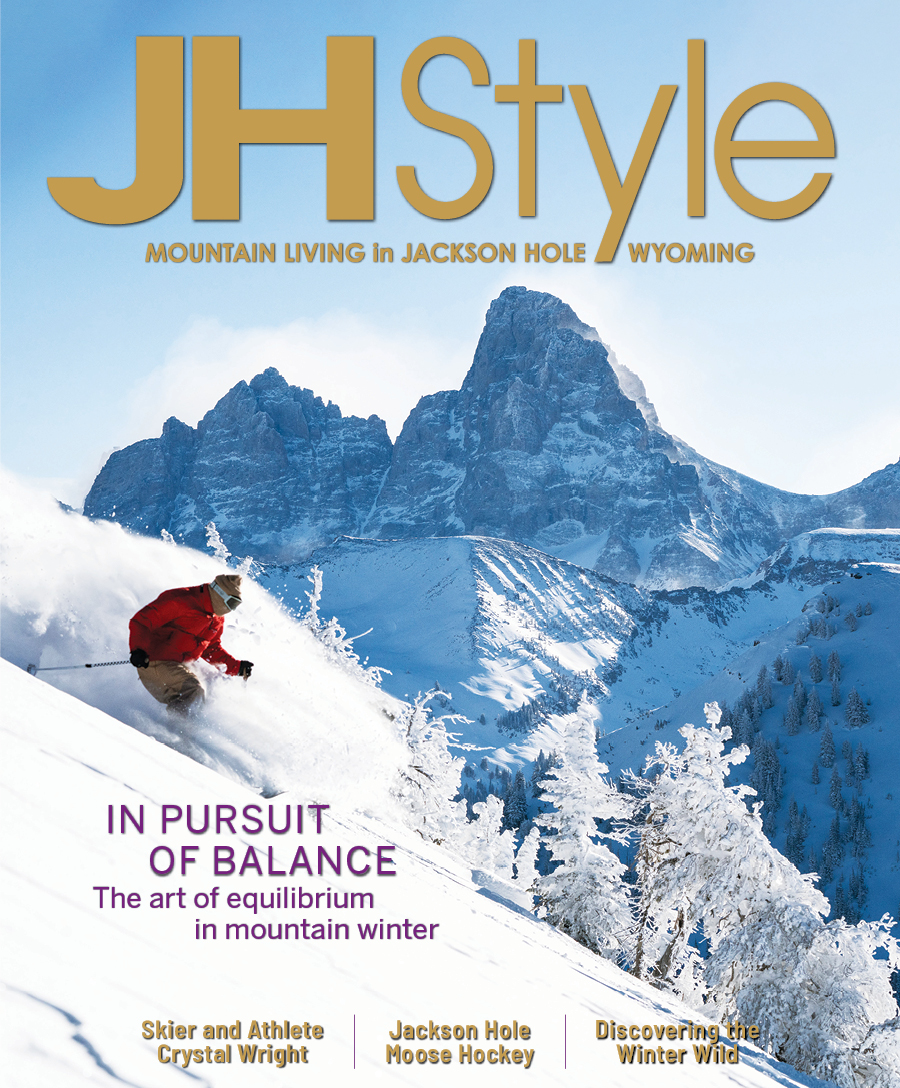

The need to be better and stronger to survive inspired a simultaneous mountain culture. Boldness, strength and skill was simply part of everyday life, from those who explored the high peaks all the way to exceedingly hardy and adventurous mail carriers, who routinely skied over Teton Pass on wooden skis in the depths of winter to bring the mail back from Victor, Idaho. And thus skiing itself became an early part of Jackson Hole culture. People began backcountry skiing with wood skis and leather boots in the Tetons, and set up car-engine powered rope tows on Snow King Mountain and Teton Pass in the 1930s.

By the 1960s, Alex Morley and Paul McCollister, two adventurous businessmen and avid skiers, had developed plans to build a ski resort like none seen before in North America and inspired by the Teton Range. The topography of the Tetons themselves dictated the terms: it would be bigger, more challenging, more exciting. The market was not those seeking to be coddled, and critics at the time thought it was an experiment destined to fail.

The most hard-core skiers embraced the long, cold winter, deep snow, and the ability to ride a tram to the alpine heights. They arrived as good skiers, and the terrain in the Tetons made them even better skiers, and built an envious bohemian lifestyle. Over the decades, famous ski racers and Nordic champions were drawn to the Tetons, and famous big mountain skiers and ski mountaineers put down stakes to call the valley home. But it’s not just the mountains that bring in the best. The heart of the culture springs from those women and men whose names will never be known beyond their home circle, who go out every day into the Tetons fueled by personal passion and spreading their inspiration.

It’s also true that the ever-present challenges to Jackson Hole are stronger than ever. Development pressure is intense, making the fight to keep important wildlife habitat and corridors intact harder, but more important than ever. A truly dedicated team of local and national conservation activists and nonprofits struggle to hold the line and improve what already exists, drawing on those far-sighted precedents set in the past. And for that wild, boundary-pushing winter athlete ethos, it’s still a hard place to live — no longer physically, but financially. Nonetheless, the pull of the mountains and the athlete culture is still irresistible to many, and those who wish to push it in the mountains find their way, as did the skiers of the past.

Thus, in many ways, it is still the landscape that drives human passion, and brings out the best in people, whether it’s speaking for nature or sending an inspirational ski line. Jackson Hole’s past has been as a place where people can find limits, personal, societal or something else, and then push them forward into a better, more accomplished future — and that is still true today. Thanks to this rich past and vibrant present, the valley has an enviable future.