Seeking refuge and finding paradise in Jackson Hole

11 Jul 2022

How the great pandemic migration is changing our landscape

Summer 2022

Written By: Lexey Wauters | Images: Mark Gocke

It is no secret that historically, Jackson has experienced a near-constant growth in population.

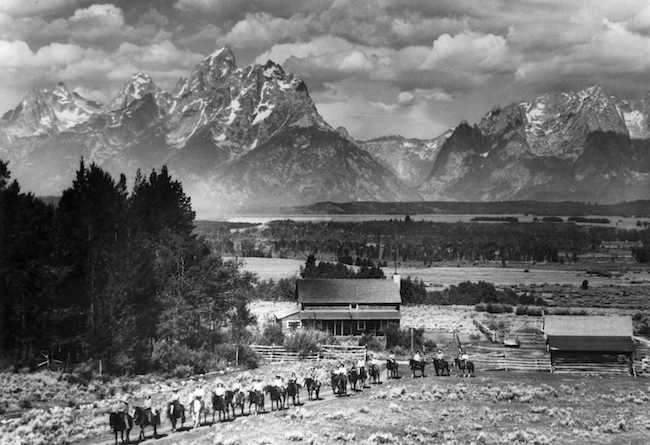

Originally inhabited by Indigenous peoples, including the Shoshone, Crow, and Northern Arapahoe tribes, the measured migration of Anglo-American settlers to the valley occurred well into the mid-20th century. And in the '50s, Jackson was a popular road trip destination for American families thanks to the national parks, dude ranches, and accessible motels. The opening of the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort in the late '60s gave the valley a two-season economy, and seasonal workers swelled the town’s population each summer and winter. Today, however, Jackson enjoys a robust year-round economy. As foundation businesses — construction, health care, and education — have grown, families have thrived. Second-home owners are spending more time in the valley and are investing in the community, providing the time and money needed to enhance the area’s cultural offerings with facilities like the Center for the Arts and events like Old Bill’s Fun Run. Teton County saw its largest growth spurt starting in 1990, growing to a population of just over 9,000 in 2003. The population growth rate slowed through the 2010s, ending at 10,709 in 2020. And then came the pandemic. Just like many of the migration pulses before it, the influx of people to the Tetons following the start of the pandemic was the result of a catastrophic event. As schools sent students home and businesses shifted to a remote workplace, people looked for refuge outside of their own communities. A good internet connection was the only requirement. Second-home owners in Jackson returned to the area and short-term rentals on VRBO and Airbnb provided a haven from urban life. As it became apparent that the pandemic was not a short-lived episode, the displaced dug in for the long haul. With any migratory surge, there is both opportunity and cost. Jackson is certainly no different. Area realtors are one population with a front-row seat to the current boom. The real estate market on both sides of the Tetons has seen rapid acceleration since the summer of 2020. “I moved here in 1972,” says Mercedes Huff, a longtime local realtor. “I love this valley — I have always enjoyed showing people this area, its beauty, the views. I’m proud of this community.” She attributes the large swaths of protected land, both public and private, for maintaining the valley’s beauty and wild nature. She says that many of the changes over the last five decades “were quite measured and reasonable. They felt safe.” That measured growth was thanks in large part to the conservation ethic shared by most longtime residents and those who migrated here in the '90s. However, she notes that those protected pieces of land have also played a role in the current real estate squeeze. “As COVID started to hit coastal cities, people were trying to escape — they were escaping urban centers. The biggie was that they could work remotely,” Mercedes observes. With limited property on the market, prices escalated. She says “it was disconcerting” how high the prices got and how aggressive the market was.

So, how did this impact current residents? Were people simply taking advantage of the real estate boom and cashing out? “Not really,” estimates Mercedes. For many sellers, the opportunity was simply an acceleration of their existing plan. Longtime residents sold to move closer to family or to escape the increasingly arduous winters. For others, it represented an opportunity to move to a neighboring community, like Victor and Driggs.

Shelby Dyer, a young up-and-coming realtor who lives and works in the Teton Valley, has her own migration story. She moved to Victor from Jackson in 2018 and had a hard time adjusting. She felt isolated and ended up moving back to Jackson. Two years later, during the great COVID migration, she returned and fell in love with the community.

These days, 80 percent of her business is on the Idaho side of the Tetons. She has found a niche in helping her peers find their first home — in Idaho. “A lot of my clients are my age! They are newly married, they’re thinking about starting a family, and buying a home was always the plan. But they are priced out of Jackson,” she explains. And, according to Shelby, they love it in Idaho. There are good restaurants, a summer music festival, lots of live music, and fewer — a lot fewer — people.

Shelby says she’s also seeing empty nesters with adult children and grandchildren move to the area. Often funded by the sale of their Jackson home, this population has been able to upsize — retiring and buying a home in Idaho.

She comments that the lifestyle in Victor feels more sustainable now. While most of her peers still commute to Jackson, she says that there is a drive to move their employment to Idaho. With the migration of businesses to the western side of the Tetons — like New West KnifeWorks, Highpoint Cider, and French Press Coffeehouse — as well as community employment stalwarts like Grand Targhee Resort, Teton Valley Health, and the local municipality, the dream of working and living on the western side of the Tetons is not far off.

Throughout history, people have migrated to improve their lives, to leave something behind, or to seek something better. The argument that life is better in the Tetons is hard to deny, and while the impact of the great COVID migration has yet to be fully understood, both great opportunity and the inevitable pitfall lie ahead. The phrase “it takes a village” has never been truer.

“As COVID started to hit coastal cities, people were trying to escape — they were escaping urban centers. The biggie was that they could work remotely,” Mercedes observes. With limited property on the market, prices escalated. She says “it was disconcerting” how high the prices got and how aggressive the market was.

So, how did this impact current residents? Were people simply taking advantage of the real estate boom and cashing out? “Not really,” estimates Mercedes. For many sellers, the opportunity was simply an acceleration of their existing plan. Longtime residents sold to move closer to family or to escape the increasingly arduous winters. For others, it represented an opportunity to move to a neighboring community, like Victor and Driggs.

Shelby Dyer, a young up-and-coming realtor who lives and works in the Teton Valley, has her own migration story. She moved to Victor from Jackson in 2018 and had a hard time adjusting. She felt isolated and ended up moving back to Jackson. Two years later, during the great COVID migration, she returned and fell in love with the community.

These days, 80 percent of her business is on the Idaho side of the Tetons. She has found a niche in helping her peers find their first home — in Idaho. “A lot of my clients are my age! They are newly married, they’re thinking about starting a family, and buying a home was always the plan. But they are priced out of Jackson,” she explains. And, according to Shelby, they love it in Idaho. There are good restaurants, a summer music festival, lots of live music, and fewer — a lot fewer — people.

Shelby says she’s also seeing empty nesters with adult children and grandchildren move to the area. Often funded by the sale of their Jackson home, this population has been able to upsize — retiring and buying a home in Idaho.

She comments that the lifestyle in Victor feels more sustainable now. While most of her peers still commute to Jackson, she says that there is a drive to move their employment to Idaho. With the migration of businesses to the western side of the Tetons — like New West KnifeWorks, Highpoint Cider, and French Press Coffeehouse — as well as community employment stalwarts like Grand Targhee Resort, Teton Valley Health, and the local municipality, the dream of working and living on the western side of the Tetons is not far off.

Throughout history, people have migrated to improve their lives, to leave something behind, or to seek something better. The argument that life is better in the Tetons is hard to deny, and while the impact of the great COVID migration has yet to be fully understood, both great opportunity and the inevitable pitfall lie ahead. The phrase “it takes a village” has never been truer.