Why is it called Jenny Lake? The story behind one of Grand Teton National Park’s true gems

13 Jun 2022

Early Indigenous peoples thrived in the Tetons, inseparable from the rhythm of the landscape

Summer 2022

Written By: Melissa Thomasma | Images: Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Offering a perfect reflection of the jagged peaks above, the tranquil, shimmering Jenny Lake is one of Grand Teton National Park’s true gems. As one of the park’s most popular destinations, it’s an iconic sight that welcomes millions of visitors every year. This breathtaking mountain lake, tucked into the folds of the glacially carved moraine at the foot of the Tetons, was named for a young woman: Jenny Leigh.

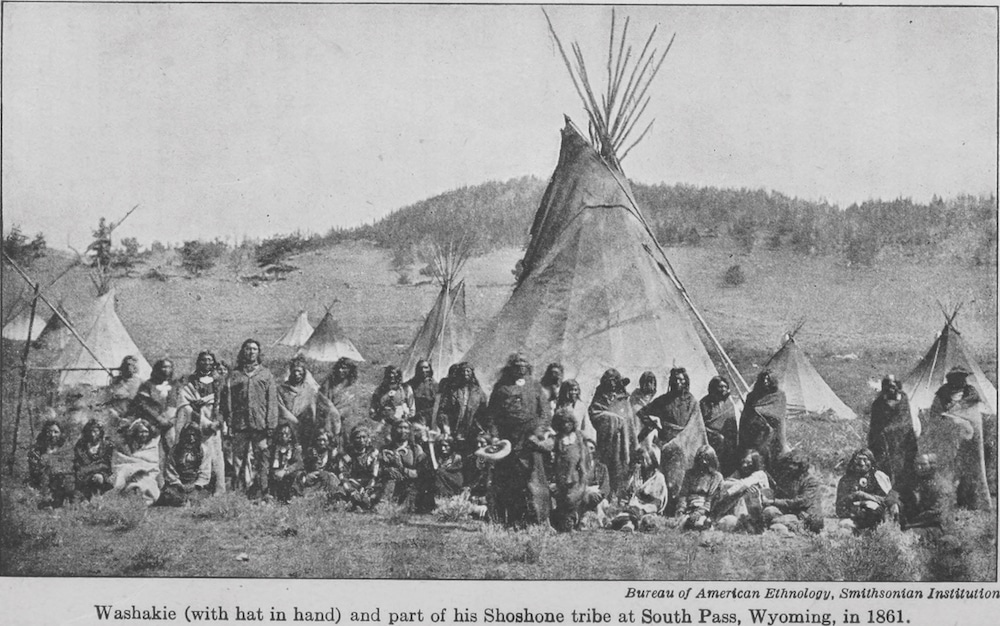

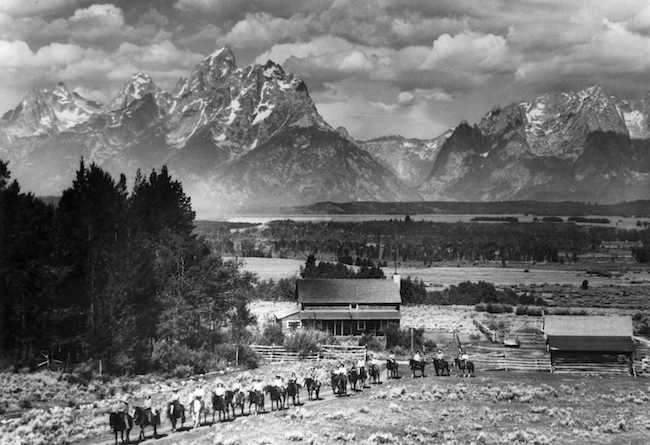

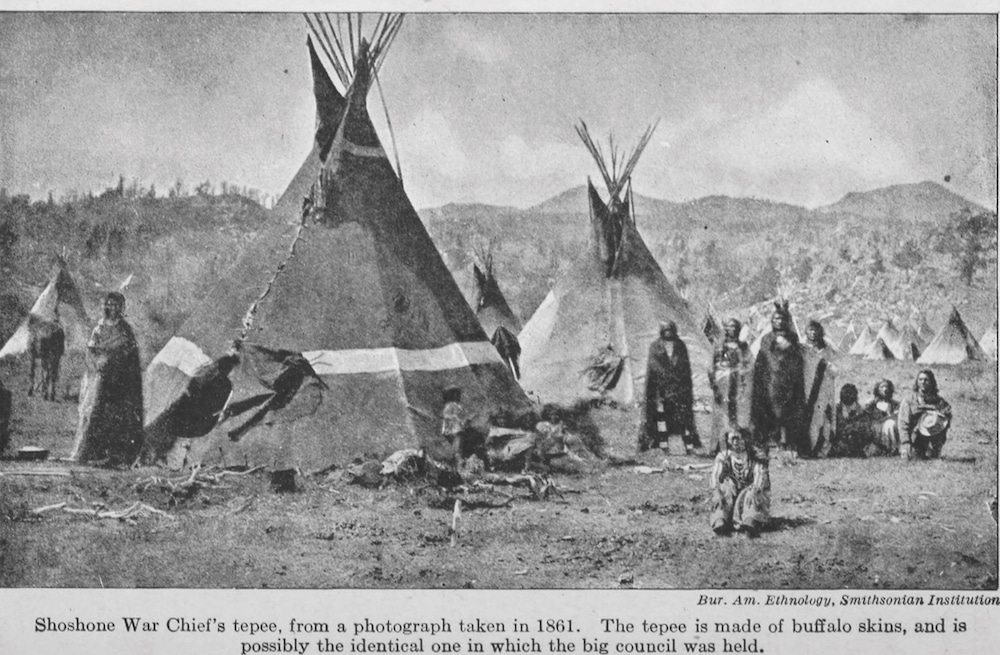

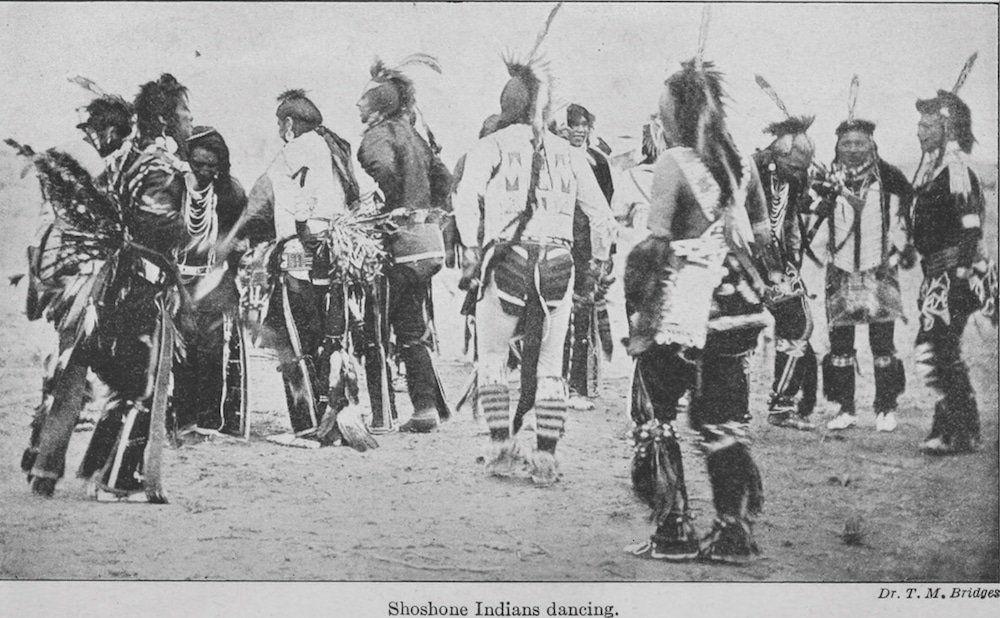

This 16-year-old Shoshone woman, whose Indigenous name has been lost to history, married a 31-year-old English fur trapper named Richard “Beaver Dick” Leigh. Based on Richard’s journals, it seems that their love for each other was authentic. The couple arrived in the Tetons in 1863 and had six children before an unthinkable tragedy struck: between Christmas Eve and December 28, 1876, Jenny and all six children died of smallpox. The lake bears her name, a remembrance of love, loss, and beauty in an inimitable landscape. Decades before Jenny and her young family perished, the shores of this crystalline alpine lake were home to her ancestors. Descendants of these first peoples — the Shoshone and Bannock bands — still reside in the region and continue to hold the landscape in the highest regard. “My ancestors chose the Grand Teton area, specifically the Jenny Lake area, seasonally. We were in proximity to all we needed. The medicines, the big game — it was all right there,” says Randy’L Teton, the public affairs officer for the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes. “Of course, it wasn’t just one place — we moved from area to area within it.” This movement, rooted deeply in the cyclical change of seasons and corresponding plant growth and animal migration, provided Indigenous people with a bounty of resources. “This valley was used seasonally,” explains Laine Thom, a member of the Shoshone tribe, who dedicated 42 years to working as a ranger in Grand Teton National Park. “Nobody was in the valley during wintertime, but otherwise, there was good hunting all year round here. They had to eat to live, and if there wasn’t food, they’d starve.” Randy’L’s Bannock ancestors followed a similar rhythm. “We lived outside, in the landscape. We were constantly hiking. Constantly fishing and hunting. We were from the Mountain Area. That’s where we thrived. We hunted, we gathered, and that was important to our everyday lifestyle.” Trout and whitefish from the rivers and lakes, plenty of big game — bison, elk, deer, moose, antelope — and smaller animals, were supplemented with camas, wild onion, wild carrot, berries, and more. The land- scape offered much more than a place to stay, it provided life itself. When the cold set in and the snow began to fall, the ice growing thicker on the frigid water, many animals traveled south. Tribes like the Shoshone and Bannock followed. And when spring returned, they did, too.

This rhythmic, deliberate existence was abruptly shattered when the U.S. government began the brutal process of forcing Indigenous people onto reservations. Those who called these lands home were forced to choose between the Wind River Reservation to the northeast or the Fort Hall Reservation to the southwest. Randy’L’s ancestors chose Fort Hall in Idaho — with its proximity to the railroad, it seemed to offer more opportunity.

Each family was given 150 acres on which they were expected to homestead, Randy’L explains. “A lot of our people didn’t understand this concept. We always felt like the landscape was everybody’s — not just ‘mine, mine, mine.’ It was a collective understanding that it was our landscape, our Mother Earth.”

Her grandparents survived the imposed schooling and held tight to Bannock, their native language. “They were forced to go to a white school, their hair was cut. They were told to speak English as citizens of the United States. Become good standard citizens,” Randy’L explains. “Despite them going through that school, they retained their language. When I was younger, they were always speaking in our traditional tongue.”

Now, she says, the number of people who are fluent in Bannock is dwindling. In collaboration with other tribal members, Randy’L works tirelessly to protect and share the rich traditions and history of her community. What hasn’t faded, however, is the profound sense of connection and love for the landscape that Shoshone-Bannock peoples carry. Laine agrees that the relationship between Indigenous people and the landscape — historically and in the present day — is not one of domination or ownership, but rather one that has embraced both the practical and the spiritual. “Everywhere is spiritual,” he says. “There is no separation between nature and spirituality.”

This inseverable bond, this wellspring of inspiration and hope, the intertwining heartbeats of life itself is still alive. Indigenous peoples, their knowledge, and their wisdom must not be banished to history books and sensationalized campfire stories.

Stories like those of Jenny Leigh, Randy’L Teton, and Laine Thom call us to deepen our understanding of the first people to call this place home. As Randy’L summarizes: “We’re the original inhabitants of this landscape. We were here before it had borders.”

When you make your pilgrimage to Grand Teton National Park, stand on the shore of Jenny Lake, and gaze across the resplendent surface that reflects the towering pinnacles above, let it resonate as more than an “Insta-worthy” view. Let it welcome you into an understanding that this place, in all its power and abundance, has always been sacred. And always will be. Offer a moment of silence in honor of Jenny’s memory.

As we move throughout this landscape — whether as residents or visitors — remember that there were many footprints on this swath of earth before ours.

This rhythmic, deliberate existence was abruptly shattered when the U.S. government began the brutal process of forcing Indigenous people onto reservations. Those who called these lands home were forced to choose between the Wind River Reservation to the northeast or the Fort Hall Reservation to the southwest. Randy’L’s ancestors chose Fort Hall in Idaho — with its proximity to the railroad, it seemed to offer more opportunity.

Each family was given 150 acres on which they were expected to homestead, Randy’L explains. “A lot of our people didn’t understand this concept. We always felt like the landscape was everybody’s — not just ‘mine, mine, mine.’ It was a collective understanding that it was our landscape, our Mother Earth.”

Her grandparents survived the imposed schooling and held tight to Bannock, their native language. “They were forced to go to a white school, their hair was cut. They were told to speak English as citizens of the United States. Become good standard citizens,” Randy’L explains. “Despite them going through that school, they retained their language. When I was younger, they were always speaking in our traditional tongue.”

Now, she says, the number of people who are fluent in Bannock is dwindling. In collaboration with other tribal members, Randy’L works tirelessly to protect and share the rich traditions and history of her community. What hasn’t faded, however, is the profound sense of connection and love for the landscape that Shoshone-Bannock peoples carry. Laine agrees that the relationship between Indigenous people and the landscape — historically and in the present day — is not one of domination or ownership, but rather one that has embraced both the practical and the spiritual. “Everywhere is spiritual,” he says. “There is no separation between nature and spirituality.”

This inseverable bond, this wellspring of inspiration and hope, the intertwining heartbeats of life itself is still alive. Indigenous peoples, their knowledge, and their wisdom must not be banished to history books and sensationalized campfire stories.

Stories like those of Jenny Leigh, Randy’L Teton, and Laine Thom call us to deepen our understanding of the first people to call this place home. As Randy’L summarizes: “We’re the original inhabitants of this landscape. We were here before it had borders.”

When you make your pilgrimage to Grand Teton National Park, stand on the shore of Jenny Lake, and gaze across the resplendent surface that reflects the towering pinnacles above, let it resonate as more than an “Insta-worthy” view. Let it welcome you into an understanding that this place, in all its power and abundance, has always been sacred. And always will be. Offer a moment of silence in honor of Jenny’s memory.

As we move throughout this landscape — whether as residents or visitors — remember that there were many footprints on this swath of earth before ours.