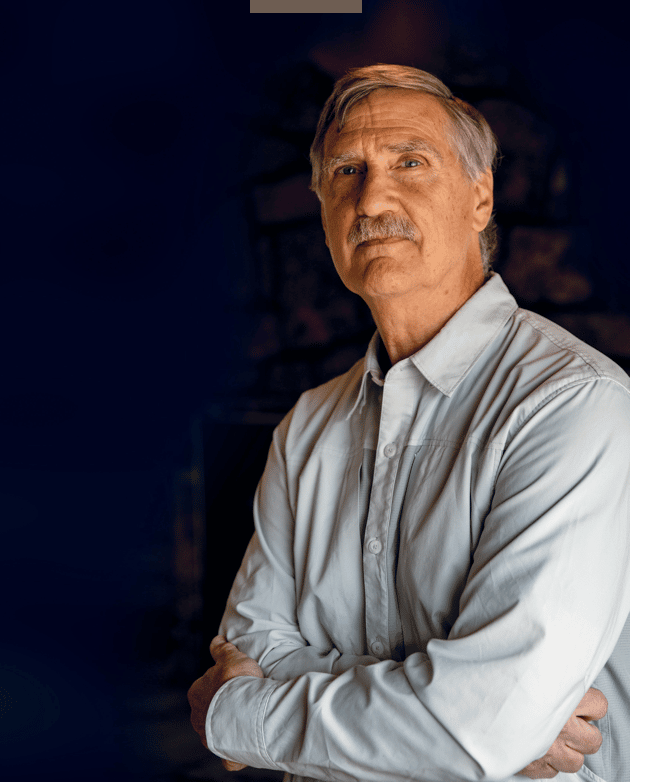

A legacy of conservation in Jackson Hole

04 Oct 2022

Bill Rudd makes a career out of mapping and protecting wildlife migrations

Summer 2022

Written By: Emmie Gocke | Images: Keegan Rice

When Bill Rudd first began studying Wyoming’s big game migrations in the late 1970s, GPS tracking collars didn’t exist.

Instead, the young scientist, who was getting his master’s degree from the University of Wyoming, would roam the Yellowstone backcountry trying to gain enough elevation to pick up radio waves from collared elk. The research he did laid the groundwork for a comprehensive understanding of elk migration routes in and around Yellowstone. And while the technology used to study migration changed drastically during Bill’s near 50-year career in wildlife biology, his dedication to wildlife and conservation remained unwavering. It all started at the age of 15, when Bill attended a youth conservation camp in northern Minnesota and volunteered with a group of wildlife professionals. “I was like, wait a minute, you can make a living doing this? And I decided I would be a wildlife biologist,” Bill says of the experience. Several years later, he got his bachelor’s degree in wildlife biology from the University of Idaho, which led to his first field job: studying pronghorn near Salmon, Idaho. When Bill came to Wyoming for his master’s work on elk migration, he decided to devote the rest of his career to studying the state’s wildlife populations and using science to advocate for their continued conservation. This led him and his wife, Lorrain, to the Greys River drainage just south of Jackson Hole, where Lorrain was completing her own master’s degree in wildlife biology and studying moose in their winter range. “We spent our first winter in a cabin with no water, no electricity, and no heat and still survived it,” Bill recalls. Next, Bill started a 30-year career with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, focusing on wildlife research, management, and conservation. He and Lorrain followed their own migration path — from Alpine to Pinedale to Saratoga to Green River to Cheyenne — as Bill moved from wildlife biologist to wildlife management coordinator, and ultimately, to deputy chief of the wildlife division where he oversaw much of the state’s wildlife management. Through it all, Bill has maintained a passion for figuring out ways to benefit wildlife. “I was always trying to get research going in the regions I was involved with, so I worked very closely with the University [of Wyoming] and Wyoming Cooperative Research Unit,” Bill says.

Through these partnerships, and in collaboration with the Wyoming Department of Transportation, Bill and his colleagues spearheaded the construction of Wyoming’s first wildlife roadway crossing in 2001, an underpass along a critical mule deer migration corridor in southwest Wyoming. Subsequent research demonstrated that the underpass reduced mule deer mortality by 80 percent.

After retiring from Wyoming Game and Fish in 2011, Bill knew he wasn’t ready to give up wildlife research and advocacy. He sat down with Matt Kauffman, head of the Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, and they came up with the Wyoming Migration Initiative, a research and public outreach organization that helps map the migrations of Wyoming’s ungulates and advocates for the protection of migration corridors.

Bill and Lorrain ultimately ended up in Jackson, although this time, they’re in a house with both heat and running water. Bill enjoys being in a place where “some of these deer in your backyard might be coming all the way from Rock Springs,” and in a community where “so many people really enjoy and appreciate the wildlife, and there’s lots of resources that people are willing to put toward understanding and solving wildlife problems.”

Bill continues to oversee a study of mule deer migration in the Uinta Mountains and serves on the board of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation and the Wyoming Wetlands Society.

Through it all, Bill has maintained a passion for figuring out ways to benefit wildlife. “I was always trying to get research going in the regions I was involved with, so I worked very closely with the University [of Wyoming] and Wyoming Cooperative Research Unit,” Bill says.

Through these partnerships, and in collaboration with the Wyoming Department of Transportation, Bill and his colleagues spearheaded the construction of Wyoming’s first wildlife roadway crossing in 2001, an underpass along a critical mule deer migration corridor in southwest Wyoming. Subsequent research demonstrated that the underpass reduced mule deer mortality by 80 percent.

After retiring from Wyoming Game and Fish in 2011, Bill knew he wasn’t ready to give up wildlife research and advocacy. He sat down with Matt Kauffman, head of the Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, and they came up with the Wyoming Migration Initiative, a research and public outreach organization that helps map the migrations of Wyoming’s ungulates and advocates for the protection of migration corridors.

Bill and Lorrain ultimately ended up in Jackson, although this time, they’re in a house with both heat and running water. Bill enjoys being in a place where “some of these deer in your backyard might be coming all the way from Rock Springs,” and in a community where “so many people really enjoy and appreciate the wildlife, and there’s lots of resources that people are willing to put toward understanding and solving wildlife problems.”

Bill continues to oversee a study of mule deer migration in the Uinta Mountains and serves on the board of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation and the Wyoming Wetlands Society.