An Extraordinary Journey

20 May 2024

The tragic and miraculous saga of the Yellowstone bison

Summer/Fall 2024

Written By: Melissa Thomasma | Images: Mark Gocke

It’s nearly impossible to imagine Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks without bison. Unlike many of their fellow creatures, they seem to be ever-present from our human vantage points. Thick herds stroll lackadaisically down park roadways, snarling traffic, and offering (from the safety of a vehicle) a shockingly up-close view of their thick fur, curved horns, and dark shining eyes.

These massive mammals — that can weigh up to 2,000 pounds and stand 6 feet tall — seem to be the untamed heartbeat of the parks themselves. And while they’ve always been here — they also haven’t.

When North America was inhabited exclusively by Indigenous peoples, bison numbered in the tens of millions. As settlers forged west, the tribes and bison faced similar brutality and annihilation. It wasn’t a coincidence. “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone,” urged Colonel Richard I. Dodge in 1867, deftly distilling the oppressive policies of General William Tecumseh Sherman and the U.S. Government at large.

The campaign was crushingly successful. Between 1830 and 1885, more than 40 million bison were slaughtered in a no-holds-barred effort to clear the plains of its Indigenous inhabitants and establish railroads. Few survived, even fewer in the wild.

“A cold wind blew on the prairie on the day the last buffalo fell,” lamented Sitting Bull, Lakota chief and spiritual leader. “A death wind for my people.”

One small herd managed to escape this grim fate, safe in the heart of Yellowstone National Park. Since its inception in 1872, hunters couldn’t threaten the bison within its borders, but park managers worried that the diminutive herd would disappear. In the spring of 1902, they counted just 23 individual animals.

In a series of wildly misguided efforts — from attempting to corral the bison and hatching plans to abduct and domesticate bison calves and beyond — those looking out for the park’s wildlife made a variety of efforts to protect the herd. They also systematically killed predators including wolves, coyotes and mountain lions in an effort to assist the bison; of course, this short-sighted management tactic triggered its own cascade of detrimental effects on the landscape, some of which are still felt a century later.

Ultimately, park managers decided it best to bolster the Yellowstone herd by importing more pure-blooded bison. Many of the bison that ended up in private herds after the decimation of wild populations had been cross-bred with cattle, and very few were genetically wild. In 1903, 21 bison traveled to the national park and were introduced to the herd. Eighteen females were purchased at $500 each from Howard Eaton, a dude ranch owner, and brought from the Flathead Res- ervation in Montana. Three bulls were purchased from legendary Texas rancher Charles Goodnight at $460 a piece (a per-animal price tag that’s roughly equivalent to $16,500 today).

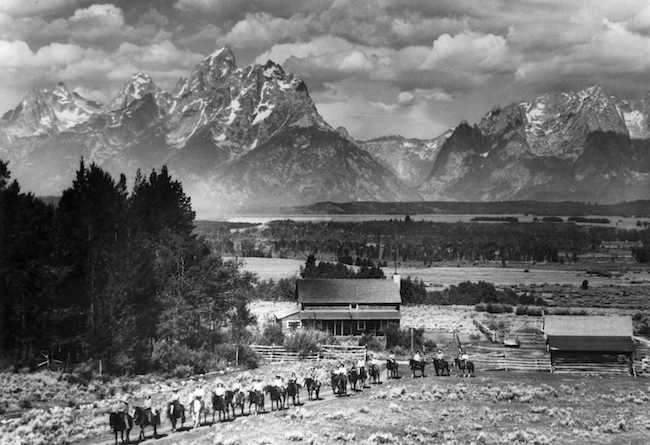

The herd began to grow, reestablishing itself within the safe confines of Yellowstone National Park. In 1948, Laurance S. Rockefeller’s Jackson Hole Preserve worked in collaboration with the New York Zoological Society and Wyoming Game and Fish Commission to establish the Jackson Hole Wildlife Park — a fenced wildlife viewing opportunity located near Moran. The collection included around 20 bison, transferred from the Yellowstone herd.

This fenced-in approach was controversial even at the time, and led to the departure of famed naturalist Olaus Murie from the managing board of the Jackson Hole Preserve.

In 1963, brucellosis — an infectious disease caused by bacteria — was detected in the herd, and all but four yearlings were removed to prevent further spread of the disease. The following year, a dozen wild bison were transferred from Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota to bolster the numbers. Perhaps the bison themselves grew weary of the fences; in 1968, the entire herd escaped the confines of the Wildlife Park. After unsuccessful attempts to recapture the rogue ungulates, managers of what had since become Grand Teton National Park decided to let them roam free.

Today, Yellowstone is home to nearly 6,000 wild bison. Grand Teton boasts another 600 or so. Experts on these bison herds confirm how special they truly are. Less than 2% of the bison that roam North America are genetically pure — exclusively the descendants of the wild bison that populated the plains so many years ago. The bison you see grazing beneath the Tetons? Wallowing near a thermal feature or geyser? They are among the 2%.

More than an exceptional conservation comeback story, the bison have returned to fill the critical roles they once held within the ecosystem. Their grazing patterns provide healthy competition with other ungulates like elk and deer, as well as recycle plant matter back into the soil. Their wallows create depressions in the earth, creating small pockets of wetland that other animals rely on. They provide critical food for predators and scavengers, from wolves, coyotes and bears to birds and smaller mammals.

As John Muir once mused, “When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world.”

Kristin Combs, executive director of the conservation and coexistence nonprofit Wyoming Wildlife Advocates, couldn’t agree with Muir’s words more strongly. “The return of bison to Grand Teton National Park is an example of how important it is for humans to right the wrongs of the past once we know better,” she says. “The valley wouldn’t be the same without these amazing creatures present; not only for their benefit to us by being quintessentially Jackson Hole, but also by the balance they bring to the ecosystem. Other species that evolved with bison rely on them in a diversity of ways. From cowbirds to native plants like antelope bit- terbrush, bison provide a slew of benefits.

“Thankfully, the previous residents of Jackson Hole had the foresight to ensure bison were returned to their rightful place, and we now have them to enjoy.”