Mountain Metamorphosis

20 May 2024

An eternal tale of transformation

Summer/Fall 2024

Written By: Melissa Thomasma | Images: Mark Gocke

There once was an ocean here. Its Cambrian-era fingerprints linger, even through the last 500 million years. The rocks of the Teton Range are some of the oldest in North America, but the mountains themselves? Toddlers, at least geologically speaking.

Thrust skyward by the forces of the Teton Fault, much of the rock in the peaks is metamorphic; gneiss and schist forged through unimaginable heat and pressure, leaving their sea-floor genesis behind and evolving into one of the planet’s most dramatic skylines.Then came the ice. Creeping and unstoppable, glaciers ground themselves through the towers of stone. When they receded, they left a newly sculpted place behind; steep valleys, rolling heaps of moraine, deep-scooped alpine lakes.

It would be easy to believe that the landscape surrounding Jackson Hole is a feature that is consistent. A backdrop. But the evidence surrounds us: it has under- gone tremendous metamorphosis. It is a fitting backstory for the cultures that have inhabited this region since. The Tetons have long enthralled humans, and as they’ve dwelled in the mountain’s shadows, have found themselves inspired to their own transformations.

Jackson Hole is, at its literal earthly core, a place of wild reinvention.

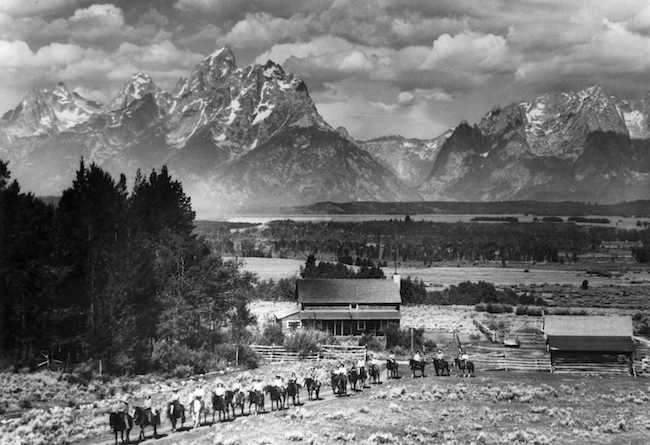

Before Wyoming was even enshrined as a state, trappers and explorers knew that there was something deeply special about the Tetons and the otherworldly geologic and thermal features of the caldera to the north. In 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant officially established Yellowstone National Park; a groundbreaking step in what would become a nationwide constellation of areas preserved for all Americans. Public lands, owned by all — stewarded carefully for present and future generations — was then something of a revolutionary concept.

The following decades saw Jackson Hole’s first homesteaders and year-round settlers stake claims in the valley. Into the early 1900s, more families arrived and tried their hand at ranching, but it proved difficult in the hardscrabble earth of the Tetons. Rocky ground twisted with stubborn sagebrush, grueling winters, and dry summers made it tough — especially on the western side of the Snake River.

And yet, something irresistible kept drawing people to the valley.

In 1908, Louis Joy and Struthers Burt had an idea. Instead of shipping beef out of Jackson Hole, they decided to welcome visitors in. The JY Ranch became the first dude ranch in the valley. Quickly followed by the Bar BC and White Grass, dude ranching blossomed into a thriving facet of the area’s economy. According to History Jackson Hole, the summer of 1925 tallied 400 locals eclipsed by 600 “dudes.”

Though these ranches typically kept a half dozen or so cows on hand — largely to enhance guests’ experience at “playing cowboy” — they welcomed guests from across the country to connect with the landscape through hunting, fishing, horseback riding and more.

Operations of this nature, however, were next to impossible when the valley was blanketed in feet of snow. As early as the late 1890s, people had been utilizing skis to transport mail and other goods from neighboring Teton Valley, Idaho; it wasn’t long before locals were hopping on the slopes for their own entertainment. In 1939, Snow King opened as the state’s first commercially operated ski facility, making the uphill part of the sport much easier.

Today, Snow King and Jackson Hole Mountain Resort host a combined 750,000 skiers each season. No longer are winters in the valley anticipated as long, grueling slogs of frostbite and cabin fever; the community’s enthusiastic embrace of boundary-pushing athleticism and passion for powder has made Jackson Hole one of the world’s premier ski destinations.

A community’s continual metamorphosis brings a kaleidoscope of impacts; opportunity and challenge, emergence and loss, growth and destruction, inspi- ration and grief. A spirit of reinvention runs deep in those who live here; it shines in a diversity of ways. People come for a visit, perhaps intending to stay for a season or two, and discover a part of themselves that somehow feels more authentic. They leave behind the buzz and glow of cities to embrace the version of their life that includes lazy summer days on the river, cozy coffee shops where one always encounters a friend, miles of meandering bike paths, and wild animals that weave throughout neighborhoods unperturbed.

They bring new ideas — akin to the national parks, dude ranches, or ski hills of yesteryear — like world-class outdoor gear and clothing, envelope-pushing culinary influences from across the globe, innovative artistic perspectives, and other passions. As their energy and dedication finds root in Jackson Hole, they find themselves forever transformed.

It’s not without cost, of course. We struggle when it comes to the fairness of who owes the tab. Our expanding footprint on the landscape demands more from the wildness around us, and her native inhabitants. Our welcoming community character leaves many puzzling over how we can ensure a roof over all heads, food on all tables.

How is it, we wonder, that we keep the best parts of ourselves while having the courage to transform?

Echoing the intensity of heat and pressure that forged the Tetons from the sediment of a sea floor, our landscape requires fire to thrive. Lodgepole pine — the towering, skinny trees that line the roads of Grand Teton National Park — clutch their seeds in cones that resist opening until heated past 120 degrees, a tem- perature that demands flame. New trees cannot begin until the forest, like a phoenix, burns.

But young lodgepole aren’t the only species that flourish in the forest’s new chapter. Vibrant grasses and wildflowers draw deer and elk to graze, small mammals and birds find new homes in the fallen trees, even the soil is rejuvenated. Disruption creates space for creation.

In Jackson Hole, we are consistently immersed in a landscape that reminds us of the limitless power of reinvention; perhaps that’s why it’s such an integral part of our community and ourselves. We trust that the heat and pressure isn’t destined to destroy, but rather to inspire and challenge us to rise. To grow. Because while what’s next isn’t entirely certain, we can ensure that it is magnificent.

EXPLORING MORE

Cultivating a deeper understanding of Jackson Hole’s natural and human history is guaranteed to make your visit even more unforgettable. Plan a visit to a few — or all! — of the area’s interpretive sites to discover fascinating stories and information.

Craig Thomas Discovery & Visitor Center

Located in Moose, Wy., the visitor center offers modern displays that explore the themes of place, people, preservation and mountaineering. Explore exhibits on your own, or join in a ranger-led program to get all your questions answered.

Laurance S. Rockefeller Preserve Center

Nestled in the heart of Grand Teton National Park, this center offers exhibits that delve into the preservation efforts that led to the establishment of the park. A junior ranger journaling program is aimed at connecting kids to nature, and a daily ranger-led hike brings visitors to nearby Phelps Lake.

Jackson Hole History Museum

In the heart of downtown, visit Jackson Hole History’s new museum campus to dive deep into the area’s rich history. With plenty of family friendly and interactive displays, the stories you’ll learn will deepen your appreciation for the area’s colorful past.

Grant Visitor Center

At Grant Village in Yellowstone National Park, this interpretive center offers a deep dive into the wildfires that reshaped vast swaths of the park in 1988. Other visitor centers in the park include the Norris Geyser Basin Museum, Old Faithful Visitor Education Center, Albright Visitor Center and more.