The path of the pronghorn in Jackson Hole

27 Aug 2022

Each spring and fall, Jackson’s pronghorn herd migrates well over 100 miles

Summer 2022

Written By: Molly Absolon | Images: Courtesy Jeff Burrell

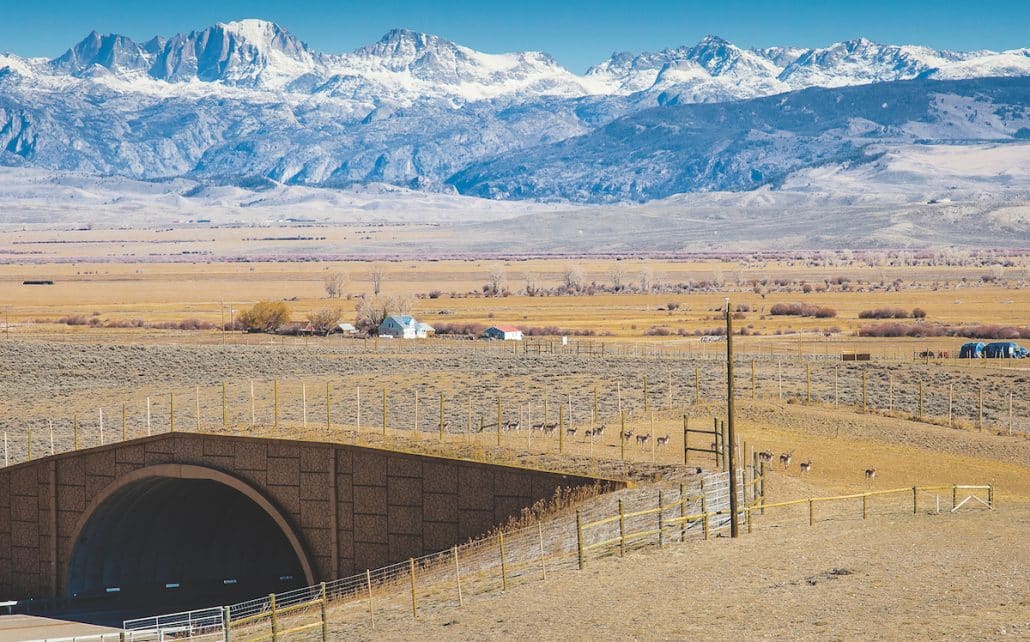

Stopped by an impenetrable fence on their journey south, a group of pronghorn, their heads bobbing up and down, mill around anxiously, unsure where to go.

One mature doe takes the lead and wanders alone along the fence line, moving forward and doubling back until she comes to a gap. Ahead of her, an overpass covered in grass arcs over Highway 191 near Cora, Wyoming. Traffic rushes by below. The doe eyes the vegetated passage warily, and then, after a moment’s hesitation, trots across, followed by her band.

“The first time they got to one of these overpasses, they didn’t know what it was,” says Renee Seidler. Renee is the executive director of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation but she spent years working as a wildlife biologist and has studied pronghorn on their migration route. “We held our breath while we watched them. They couldn’t see the gap in the fence until it was right in front them. I’m sure there was a method to the madness of their searching, but it’s hard to know what was going through their heads.”

The pronghorn on the overpass — part of the greater Sublette Herd, which numbers around 40,000 and ranges from Interstate 80 to Jackson — was moving from its summer home in Grand Teton National Park to its wintering grounds in the Green River Valley. Roughly 300 to 600 pronghorn make this 160-mile migration each fall and spring. It’s one of the longest documented land migrations in the lower 48 states and the first to be a federally designated migration corridor.

The “Path of the Pronghorn” was discovered during mitigation for energy development on the Pinedale Anticline in the early 2000s. Wildlife biologists collared pronghorn, and the resulting data allowed them to map the animals’ movements. What they discovered was surprising.

“The Sublette Herd has animals that spend their entire lives on the Mesa [near Pinedale], and there are also parts of it that migrate east and west near Big Piney, going up into the Wyoming Range for the summer and moving downslope as winter progresses,” says Brandon Scurlock, a wildlife management coordinator for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department in Pinedale. “And then you have a small group that uses the Path of the Pronghorn.”

“I find it fascinating. The herd has different survival strategies. Some are year-round residents in the Green River Valley, some go up into the mountains, and then there are the long-distance migrators,” he says. “As a herd, having all these different strategies is good in the long term, especially in light of climate change. It makes them more resilient.”

Before European expansion into what is now the western United States, scientists estimate that 30 million pronghorn, the fastest land mammal in North America, roamed the sagebrush steppes. By the end of the 19th century, 99 percent of those animals were gone. Today, the species has stabilized, and Wyoming is considered to be a stronghold for the pronghorn, with as many as 400,000 animals residing in the state. But the migration routes they’ve traveled for thousands of years are critical to their survival, and threats from human development and habitat degradation associated with climate change and invasive species could jeopardize their success.

The Path of the Pronghorn was designated by the Bridger-Teton National Forest in 2008. It protects the forested migration corridor that travels up the Gros Ventre River, over 9,100-foot mountain passes, and down to Green River. Beyond the forest boundary, the migration path goes through a patchwork of private land. It is only through coordinated efforts between landowners, the Bureau of Land Management, the Wyoming Department of Transportation, and conservation groups that this section remains viable for the migrating pronghorn. Those efforts include fence mitigation and highway over and underpasses that allow the pronghorn to cross through traffic safely.

“In Wyoming a lot of our big ungulate herds migrate in order to survive,” says Kristen Gunther, program director at the Wyoming Outdoor Council. “These long-distant migrations link the iconic landscapes of Wyoming, connecting different types of habitats and communities, and emphasizing how interconnected our ecosystems are.”