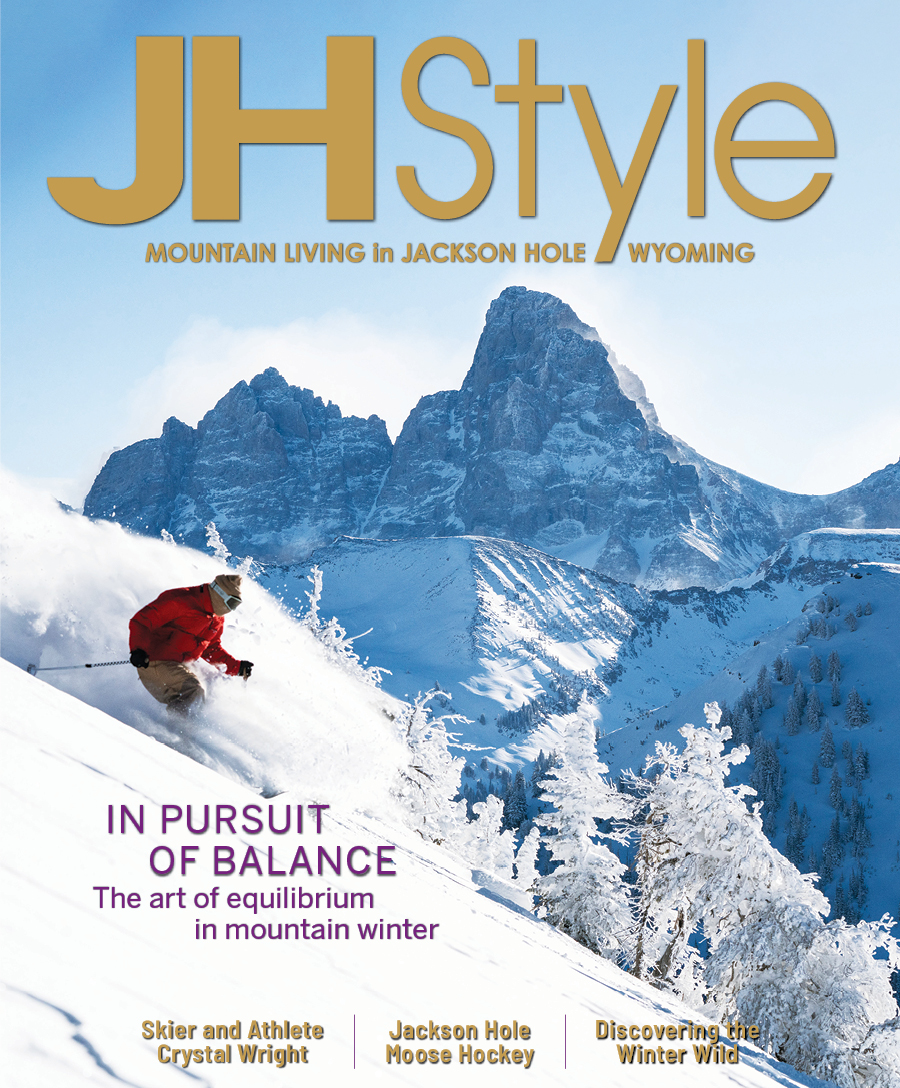

The Soul of Teton Pass

24 Nov 2025

Teton Backcountry Alliance is protecting a local gem, one skier at a time

Winter/Spring 2026

Written By: Phil Lindeman | Images: Andy Cochrane

If you’ve spent time on Teton Pass in the past three decades, you’ve most likely met Jay Pistono and his crew. They’re hard to miss in bright jackets with stitching that reads, “Backcountry Ambassador.”

Depending on the day, you’ve also met upwards of 500 other powder hounds scrambling for turns at one of the most accessible backcountry zones in the Rocky Mountains. Popular areas like Glory Bowl are a bootpack away from the main parking lot, which fits only 50 cars when plowed to the maximum.

The peaks and pow stashes haven’t changed since 1977, when Jay arrived from Illinois, jobless and penniless en route to Canada. (He could hardly even ski back then.) But the scene at Teton Pass has changed. A lot.

“The equipment, the athleticism, the vibe – people talk to each other and the word gets out – and this area has more appeal to it than ever before,” Jay said. “You have all these people getting good medicine on the Pass. You can’t let a few monkeys ruin everything for everyone.”

Humble beginnings

Teton Backcountry Alliance, which oversees the pass ambassador program, started more than 30 years ago with Jay and dog poop.

“Back then you couldn’t ski the last 200 yards in the spring without skiing through dog shit,” Jay laughed. This led to a chat over beers with a few U.S. Forest Service rangers, who offered Jay a paycheck and the chance to do something about that poop.

“They said, ‘We think we can pay you for this,’ and I was like, ‘I’m your man,’” Jay remembered. “This is still a labor of love. We do this because we love Teton Pass. We’d be there anyway.”

Tait Bjornsen would definitely be there anyway. Before she was named program director and lead ambassador for the Alliance, she was skiing the pass with her dad at 7 years old. Before then, she knew Jay as the pow chaser next door.

“Jay was the first person to bring to our attention how, this is a privilege to ski here, not a right,” Tait said. “If we want to keep skiing here we have to be flexible. We have to listen to each other more.”

Protecting the Pass

Ambassadors are the frontline defenders of the Pass. This season, 10 are paid. The rest are volunteers. On most winter days they arrive at dawn, armed with friendly reminders about parking, patience and avalanche awareness.

“What we’re experiencing right now is overloving and overcrowding at a place that is so small, but is really so big,” Tait said. “Lots of people get jammed up in these parking lots and it can cause problems.”

For the state of Wyoming, a bigger issue is the terrain surrounding Jackson Pass. Hundreds of skiers and workers travel Highway 22 daily. When avalanches strike they can have devastating and potentially deadly consequences. In December 2016, a skier likely sparked a slide that buried a Jeep. Other slides have buried cars as recently as 2019 and 2020. No one has been injured, but these incidents highlighted the need to mitigate human-triggered slides before they start.

“We’re not just at the parking lot,” Jay said. “Some of our most meaningful contacts are talking to people on the trails. We are efficient about our communication. We won’t talk to you for a half hour. It’s more like a minute or two.”

In recent years the Alliance has added other programs, like a free skier shuttle, avalanche courses, a weekly show on KHOL radio and the Coal Creek Beacon Parks, where you can practice your avalanche search skills.

“It’s not just, know ‘before’ you go,” Jay said. “It’s know ‘as’ you go. It doesn’t take a ton of research. If you make good decisions a habit, you come home with a smile on your face.”

For years now Jay has tried to retire, but they keep bringing him back. He doesn’t mind. Like he says, he’d be there anyway. But this season, he promises, will be his last. And he’s leaving his legacy in good hands – Tait’s.

“If you are waiting for someone else to do the job, stop,” Jay said. “It’s on us to protect these places. I don’t care if we are best friends. I’m not worried about hurt feelings if it keeps that access open. People can process hurt feelings. I hope my legacy is, ‘That guy did a good job up there. He helped keep this open.’”